Island Contemporary Art

Articles about Contemporary Art of the Scottish Islands.

‘Un-boarding’ the Window

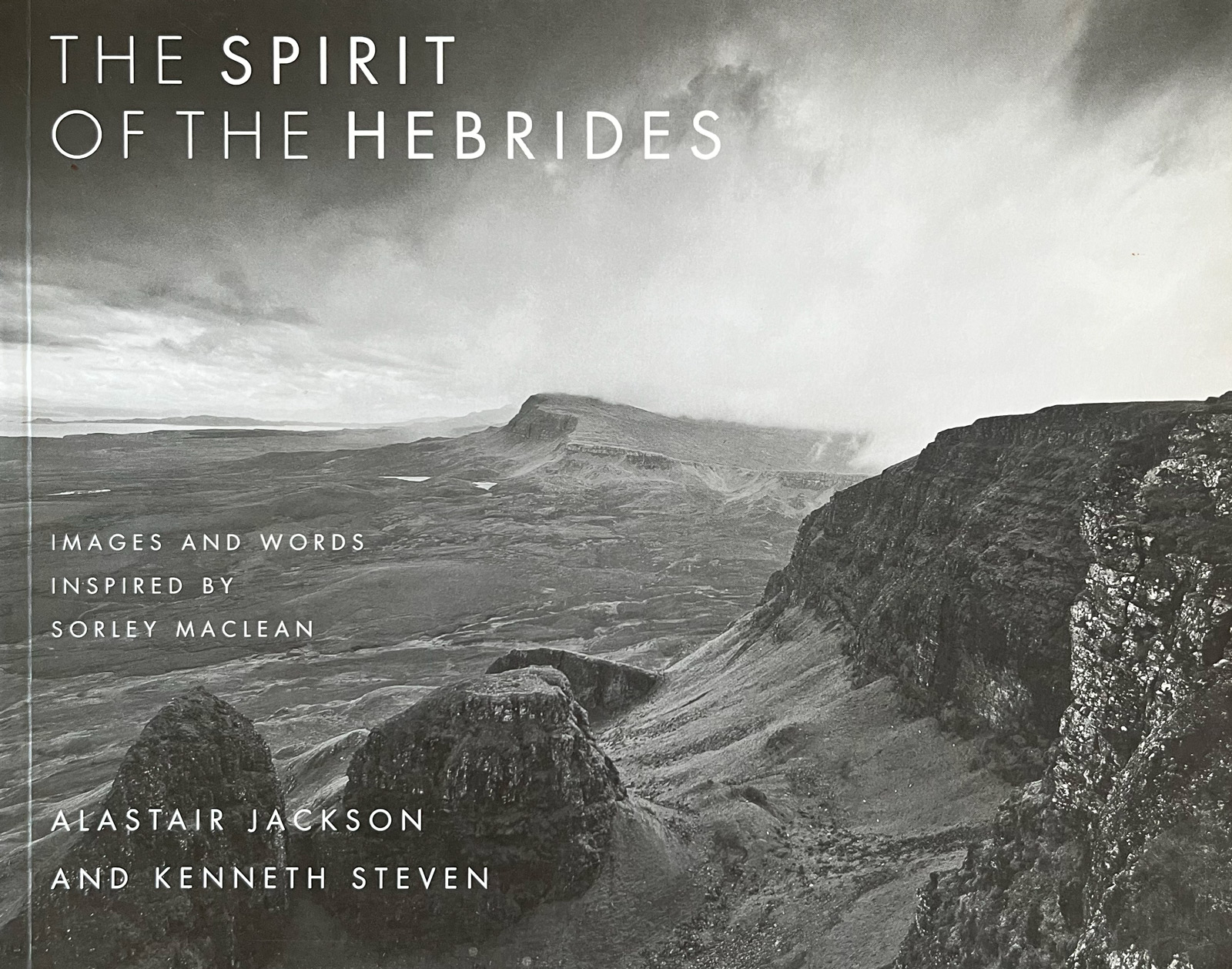

“Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig trom faca mi an Àird an Iar. The window is nailed and boarded through which I saw the West”. From ‘Hallaig,’ by Somhairle MacGill-Eain (Sorley MacLean). Written ...

Marie-Claire Cameron : 26/Nov/2025

View Article

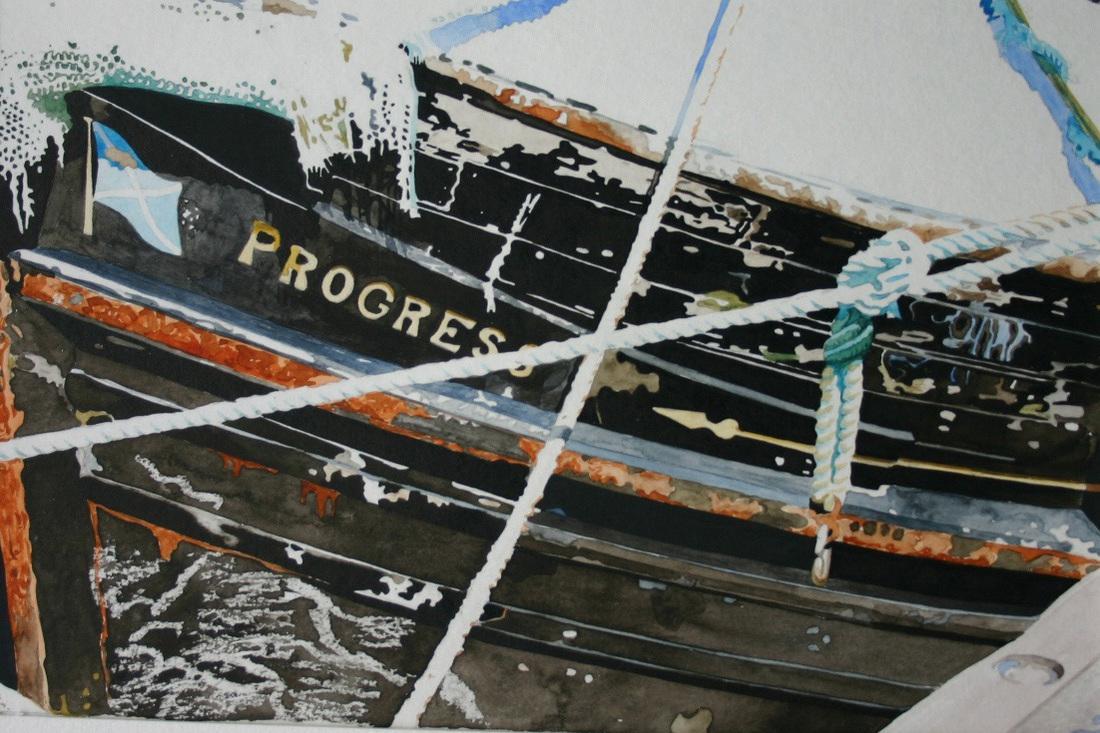

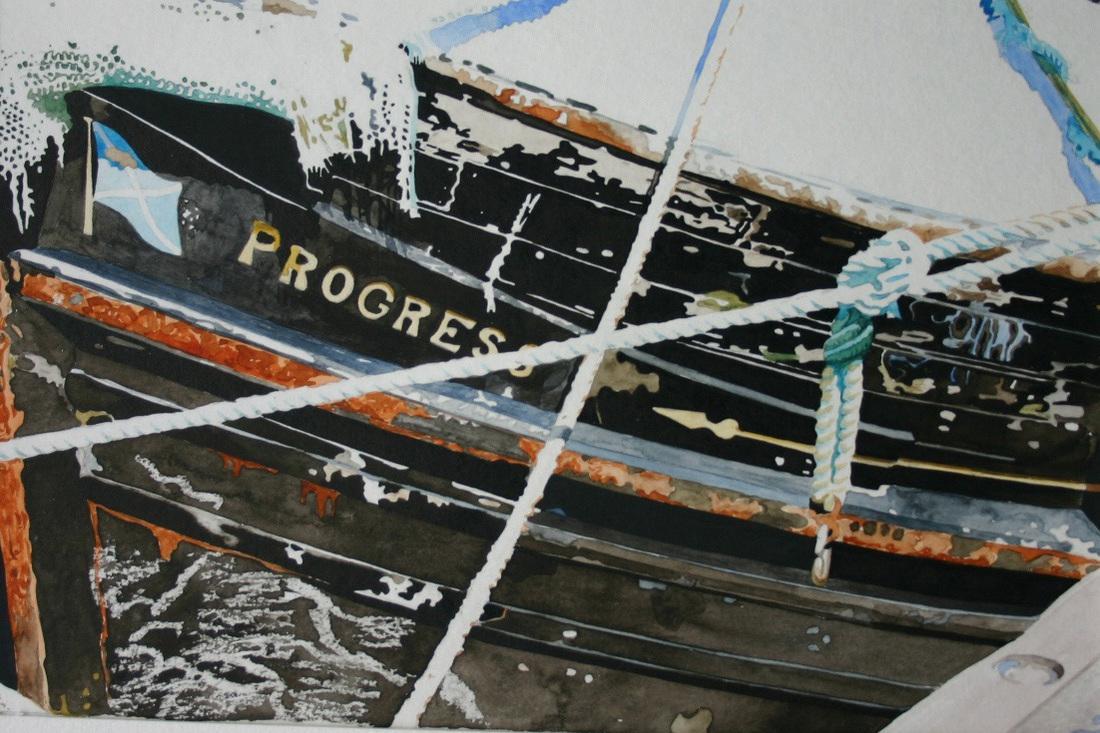

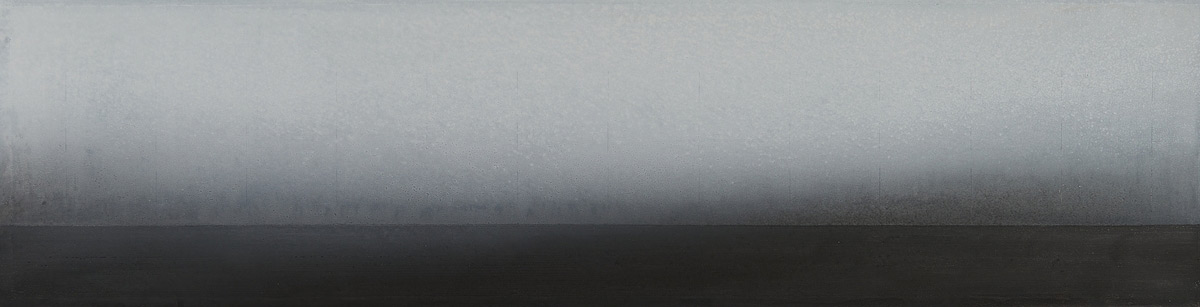

Ishbel Murray, Progress, c. 2009. Oil on canvas. © Ishbel Murray.

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

‘Un-boarding’ the Window

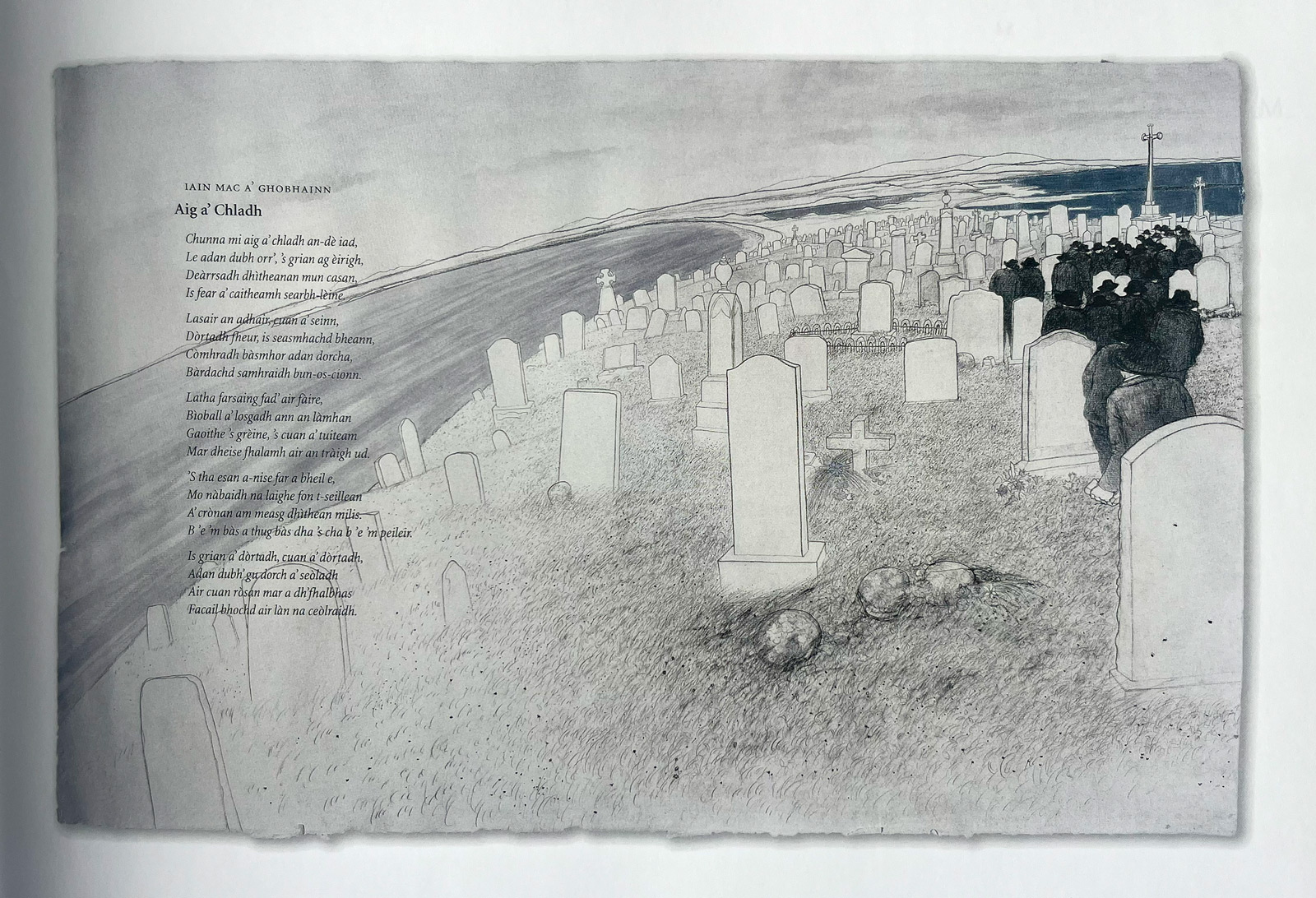

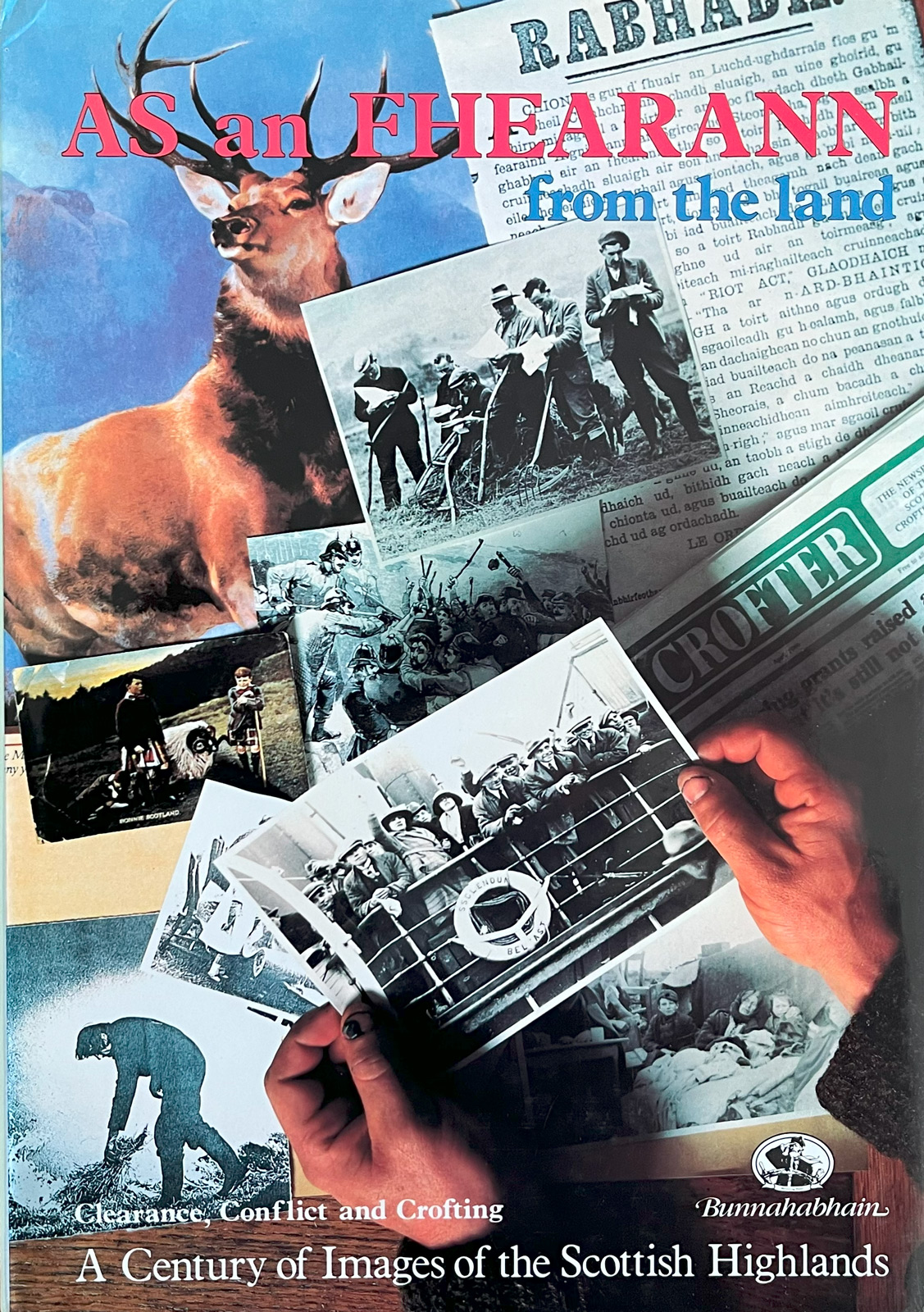

In his poem ‘Hallaig,’ Sorley MacLean describes a house in Raasay, the Island where he grew up.[i] He describes the windows of the house, in the village of Hallaig, as being sealed by wooden boards, then later in the poem speaks of a deer “sniffing at the grass-grown ruined homes,” the growth of grass an indication of how long it has been since anyone lived there.[ii] Which would be one-hundred years, as the poem was written a century after the village was subjected to the Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal/ Banishments, or Clearances, in 1852.[iii] Since it was first published, the poem’s image of a boarded house has become symbolic of the Clearances while simultaneously immortalising Hallaig as the thriving hub it was. MacLean conjures up an image of a village populated with plenty of big characters, people going about their day and young girls giggling as they walk home. To a home now sealed up, the giggling girls’ stories and their lives now a memory.

Stories and memories which lay hidden until a handful of contemporary artists started metaphorically ‘un-boarding’ empty houses across the Outer Hebrides. The artists were Moira MacLean, Anne Campbell, Marnie Keltie, Ishbel Murray and Mary Morrison. Moira MacLean, of Lewis born and bred, quite literally tore through empty homes, describing her artistic practice as ‘raiding’ crofts.[iv] She descends upon abandoned sites across Lewis, ripping off scraps of wallpaper (see photograph below, image 1). A self-proclaimed ‘pirate,’ she calls the scraps ‘silent witnesses,’ which rightly acknowledges that these bits of wallpaper have been ‘flies on the wall’ in the lives of all those who inhabited the houses over the years. The wallpaper bears testament to domestic stories, stories of the everyday acts that made up the lives of the families. Domestic histories (or her-stories) do not always make it into history books but are valued by MacLean when they are incorporated into her artwork (see image 2, which shows Moira MacLean’s studio with the pieces of wallpaper ready to be used as material for later artworks).

Image 1: Moira MacLean, ‘Raiding.’ Photograph. © Moira MacLean.

Image 2: Moira MacLean in her studio. Photograph © Moira MacLean.

In MacLean’s ‘Memory of a Village’ mixed media piece, she puts the wallpaper scraps into an image of the village which brings the empty homes she ‘raided’ to life - just as Sorley MacLean’s poem does for Hallaig. In her artwork, the lights are on in every house, the roofs are well maintained and their exteriors painted a crisp fresh white – the homes are loved and looked after. The wallpaper scraps she includes brings the very real memories to her village scene. By choosing wallpaper as her material of choice, and not, say, evidence of outdoor work, she specifically references the female tending the hearth at the heart of the home. In her Buisneachd installation of 2012, she takes the idea of excavating domestic stories further by representing the interior of the empty blackhouse within the space of An Lanntair (see image 4). The installation revolves around a great wooden hearth whose wooden frame - which appears ever more ‘homely’ contrasting against the white cube exhibition space - is adorned with a colloquial, heart-shaped decoration suggesting that home is where the heart(h) is. The knitted pink breasts, placed comically on the side-table, humorously references just one of the many labours of love which would have taken place in the home. Labours which sustained village life. By bringing the home into the context of the art gallery, she brings domestic village life in Lewis under the scrutiny of a critical lens: asking us to really consider the stories these familial objects hold.

Image 3: Moira Maclean, Memory of a Village #12, 2012. Mixed Media. © Moira MacLean.

Image 4: Moira MacLean, Still from ‘Buisneachd,’ 2012. Mixed media. Shown at An Lanntair, Stornoway. © Moira MacLean.

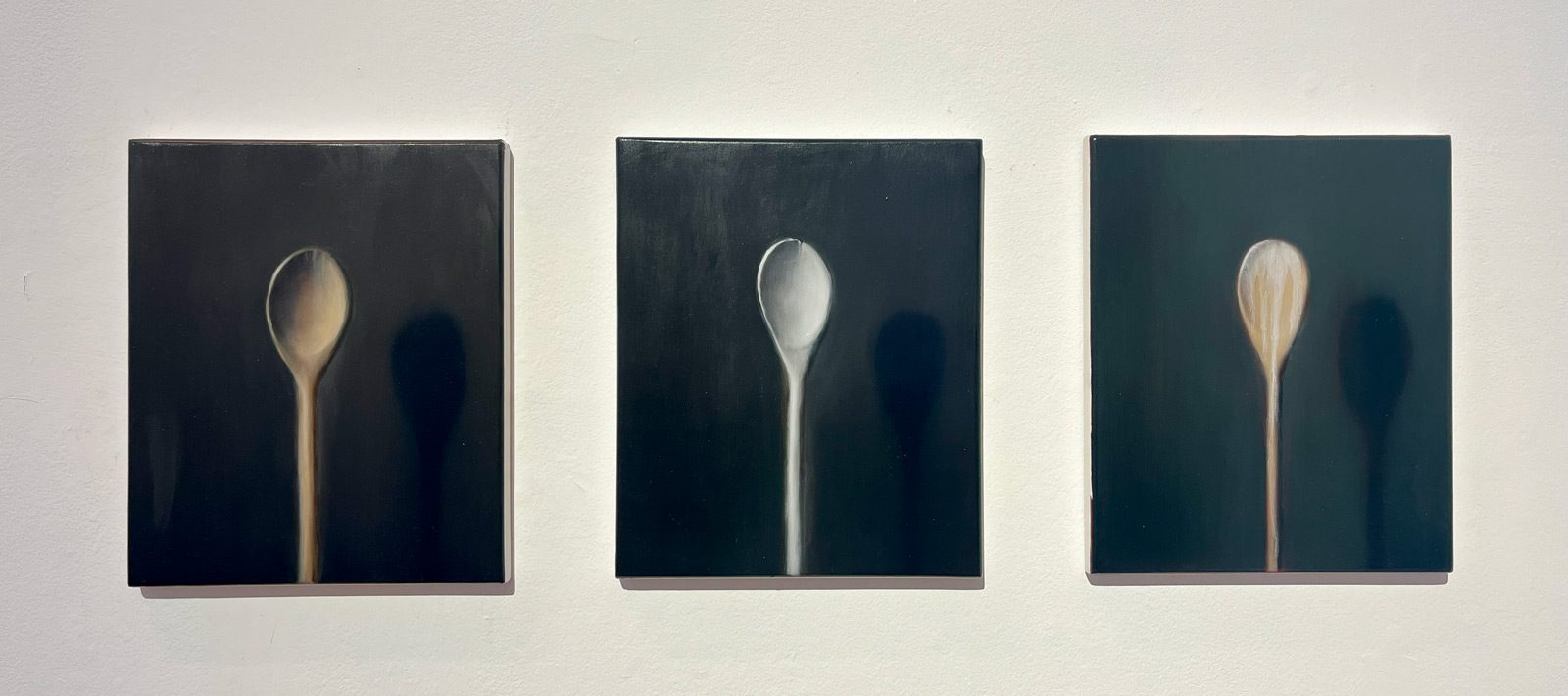

Like Moira MacLean, Ishbel Murray scrutinises objects from within the house to tell stories in her artistic practice. In Murray’s installation at the ‘Astar: Glen Tolsta’ exhibition of 2012, at An Lanntair, she (re)created the setup of a blackhouse dresser. Such a dresser might have displayed items of fine china or special trinkets and so, in the presentation of her work, the china teacups of her ‘Fragments’ series sit in front of painted porcelain, which mimics china plates (see image 5). The effect is that of a dresser display. The Ulaidh/ Treasure plates (see image 6) are another take on the sort of plates Grans might have adorned their dresser with. This work was inspired by blue porcelain ceramic fragments she found on the beach. The title of the works exhibits her practice of imagining the ‘treasures’ these fragments came from. She created the Ulaidh artworks for the ‘Astar’ installation with the aim of sparking a connection with Glen Tolsta. ‘The Glen,’ an area whose first inhabitants only arrived in 1843 and were the displaced individuals who had been relocated from Park. (After more profit was seen in sheep farming on Park land). Each plate has been carefully hand painted with the portrait of individual World War II servicemen from The Glen. The portraits were based on roll of honour photographs taken of the men before they departed. In great detail, she captures exactly how they sat for their photographs wearing their clean, crisp brand-new merchant navy uniforms. The smoothness of the oil paint emphasises the youth of the young men’s faces, highlighting just how young they were when they left.

Image 5: Installation shot from ‘Astar: Glen Tolsta’(shown at An Lanntair) featuring Ishbel Murray’s Conversational Fragments. Porcelain on wood mounts, 2012.

Image 6: Ishbel Murray, “Ulaidh/ Treasure” Portraits for the Astar: Glen Tolsta exhibition, 2012. Oil on Ceramic. 26cm. © Ishbel Murray.

Tolsta is where Murray’s mother’s people are from and her late mother’s father, Iain, grew up in The Glen, so with her the choice of material she is grappling with a very personal history. There were twelve plates in the Ulaidh installation, all wall mounted in a row, taking up some three to four metres of space. The sheer length of the row and the space it occupied really impressed upon the viewer the scale of the loss of population to the Glen (and to the whole island of Lewis). The plates make a socio-political comment on the loss of ways of life in the Glen after World War II, which saw a shift in the way people worked and where they lived. The men of the portraits were the last generation of ‘Gleannaich,’ to be of Glen Tolsta born and raised. Murray’s work, then, is a commemoration of these young men. It is also a commemoration of that way of life. The story is one of great loss but, arguably, it is transformed through Murray’s art into an act of remembering and celebrating the men’s lives. She does this by rendering their portraits in a vivacious cobalt blue and by accentuating their expressions, so that they seem to come alive in the portraits. They feel very present.

The portraits are painted onto porcelain with a Chinese willow tree pattern, a trend at the time (hence displaying such pieces on a dresser). But the pattern connotes serious political implications. It references the endeavours of the proprietor of the Isle of Lewis from 1843-78, Sir James Matheson, a Highland born (Lairg) gentry-man, who earned his fortune trading tea in China with his partner in their combined firm Jardine, Matheson and Company Ltd. Matheson bought the Isle of Lewis in its entirety in 1844 and, having profited from the opium wars his company helped orchestrate in tandem with another company, it was under his and the continued rule of his wife, Lady Matheson, that some of the largest clearances of people occurred on the Island. Murray states that she hoped the piece would make the viewer consider Matheson for his treatment of the locals of Lewis: his extravagant building of Lews Castle on his newly bought Island at a time when many Islanders, like those who moved to Glen Tolsta, struggled to attain much needed resources.[v] The story of James Matheson has parallels across the rest of the Gàidhealtachd, as many other landowners benefitted from wealth derived from the colonies, and many estates were sold to beneficiaries of colony derived wealth between 1790 and 1855 – the main period of evictions. Murray’s work indicates just how nuanced and complex a colonial situation there was in both Lewis and the greater Highlands and Islands at that time.[vi]

The teacups shown in Murray’s installation for the ‘Astar’ exhibition not only represent the furnishings a blackhouse would have contained but suggest the language and culture which would have filled the home. Murray’s series of teacups all feature a landscape painting on the side of the mug for decoration. They are also all adorned with a proverb or quip written in Gàidhlig within the rim of the cup, to be seen while drinking. For instance, in Cho teth ri gaol seoladair (see image 7), there is a painting of a coastal scene accompanied by the text Cho teth ri gaol seoladair which translates as ‘something which is extremely hot.’ Or, in the (much more entertaining) literal translation, ‘as hot as a sailor’s relationship.’[vii] Here we have fishing community life, familiar speech and humour tied together and presented as inextricable from the language. A poignant reminder that languages are so much more than just words. As Iain Crichton Smith says, “he who loses his language loses his world,” by which he means that keeping a language thriving is part of keeping a culture alive.[viii] (The language has persisted, albeit in reduced numbers and despite Imperial ‘Improving’ intervention, in particular since the 1872 Education Act banned any teaching not conducted in the English language).[ix] Little jokes and seemingly mundane proverbs are praised as the cultural artefacts they are, in Murray’s artwork. Supporting the use of Gàidhlig is something that Murray values, having grown up with Gàidhlig speaking parents and then going on to teach the language in Glasgow. Murray actively seeks to keep the language alive and spoken by selling these teacups at reasonable prices to the general public (via accessible online shops) to facilitate the tea drinking and conversation that these cups celebrate.

Image 7: Ishbel Murray, Cho teth ri gaol seoladair from ‘Conversational Fragments’ series. China Teacup, painted. c.2012. © Ishbel Murray.

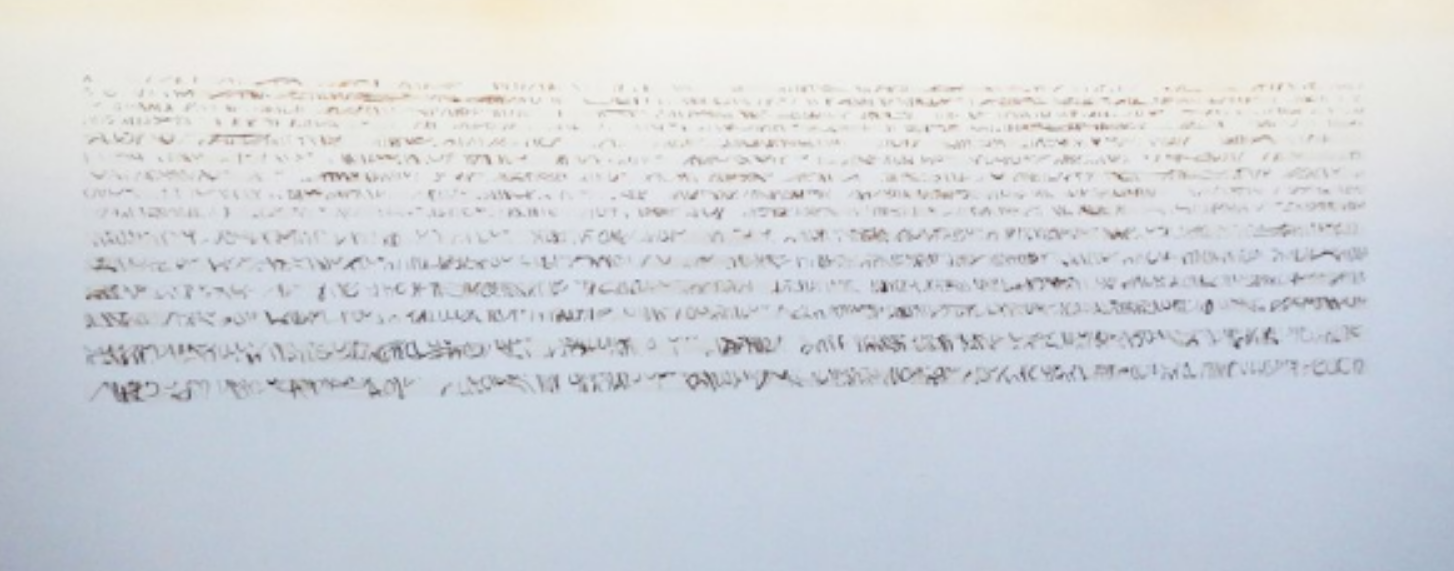

If Murray and MacLean excavated the inside of the black-house, Marnie Keltie finds fragments of material from outside the house to tell its stories. Stories which explain the historical context of boarded houses across North Uist, where she lives and works. In her Kelp Ink Wall Drawing (see image 8), she paints a hand-calligraphed story using her home-made kelp ink. With her ink she paints a story explaining the relationship between the Kelping Industry’s demise and the clearances on Uist. The story she paints, word for hand calligraphed word, was told to her by her neighbour and local intellect Alasdair MacDonald. It is a mythical story, yet one which reflects a very real incident regarding farmer Hugh MacDonald - who had brought the Kelping Industry to the Hebrides in 1735 and who owned the seaweed rights on Rònaigh and Baleshare.

Image 8: Marnie Keltie, Kelp Ink Wall Drawing, 2012. Kelp Ink on Plaster wall. © Marnie Keltie

The kelping industry was ‘a goldmine for landlords.’[x] Some seventy percent of the populations of the Uists and Bernera worked at least seasonally on the kelp farms. However, the kelp price plummeted when a cheaper alternative to potash (what the kelp was used to make) could be found in Spain. Therefore, in 1849 Lord MacDonald would evict some 1300 people from Uist as the kelping was no longer profitable (to him). The cruelty of this exploitation is reflected in Alasdair MacDonald’s mythical tale: Hugh MacDonald tricks the seasonal kelp worker in a symbolic horse and dog race so that he and his horse may win and keep the riches, killing the Skye man’s dog to do so. Keltie writing this story in kelp makes it that much more visceral to the reader. Furthermore, the labour intensive process of creating kelp ink (the collecting of kelp from the shore, the lugging of kelp back up the beach, the boiling down of the kelp and the constant stirring and attending to the pot over hours) reflects the arduous labour of creating potash with kelp, which whole families would have taken part in, tending the kelp kilns or pits for up to eight hours.

If Sorley MacLean fulfilled the bardic role of transmitting the history of the clearances through the symbol of the lone house stood on Hallaig, Keltie continues in the same vein. She peers into the past of the now cleared ruins on Rònaigh and re-tells the history for a wider audience. The story told in the Kelp Ink Wall Drawing is noted down word for word as recounted orally by Alasdair MacDonald, considered a modern day bard of sorts. In decolonising terms, MacDonald’s words re-write the history of Rònaigh. He writes back against the Imperial Narrative, still taught to school children up until the 1970s, of how the Clearances were a series of ‘Improvements,’ unfortunate but necessary in the name of economic ‘progress.’ This was the (colonial) language of the day. Keltie’s work questions the authority of who writes these histories, who writes Scottish children’s textbooks. Her work reinstates the authority of local systems of knowledge: by presenting the oral history in the format of the Institutional preferred form of knowledge – the written word. As such, the viewer is asked to consider who has customarily held the discursive authority to tell the history of the Hebrides.

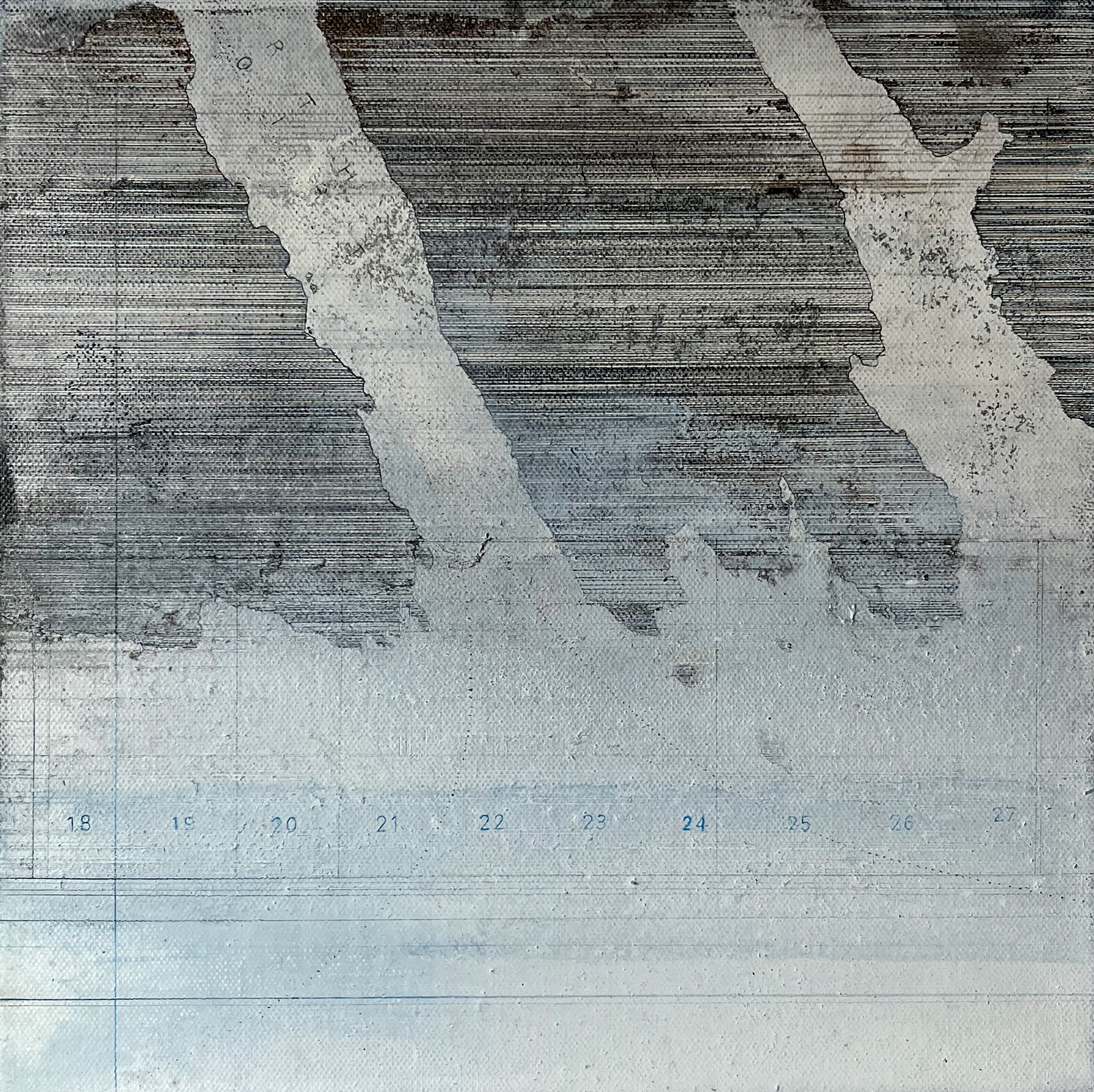

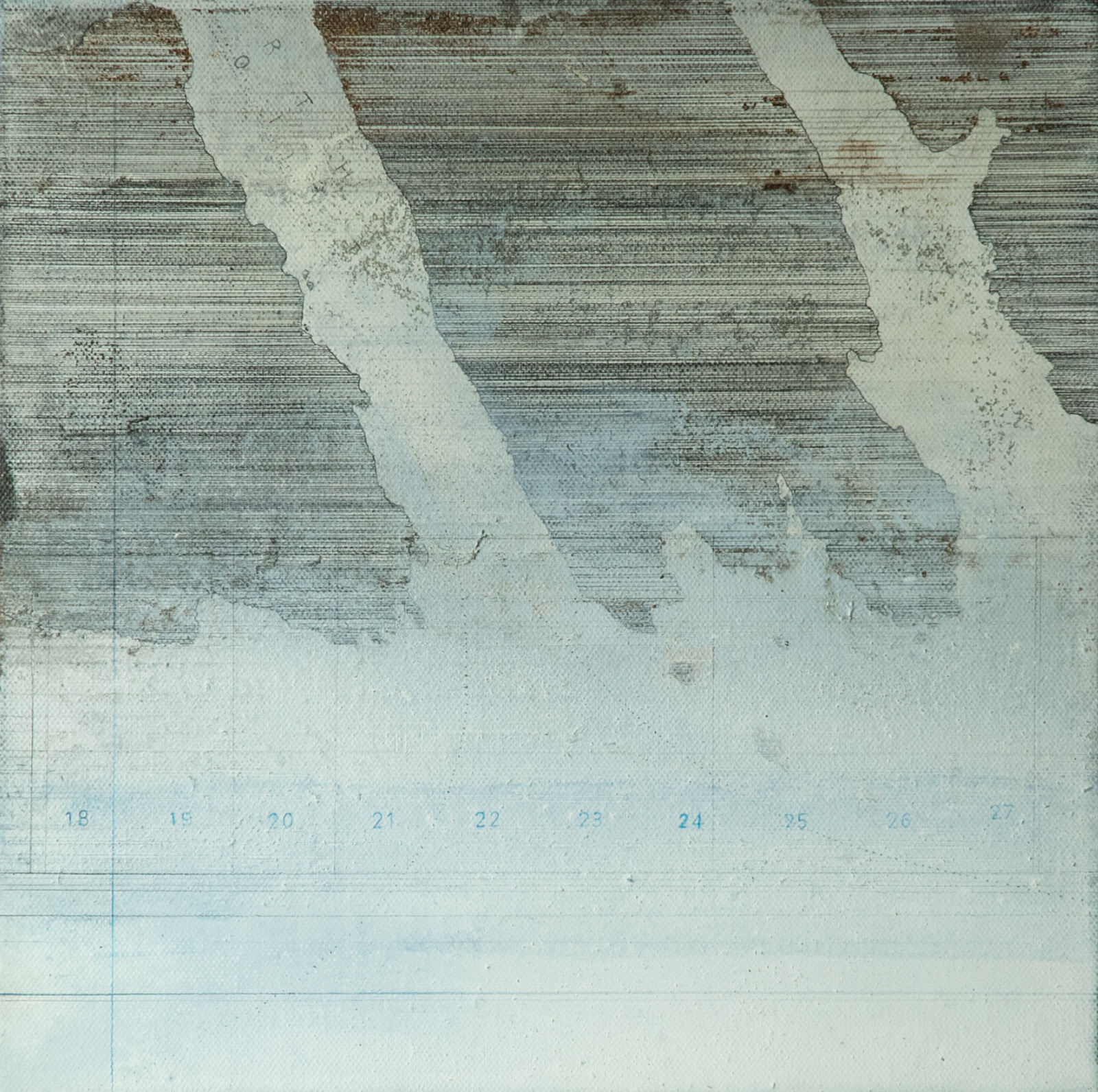

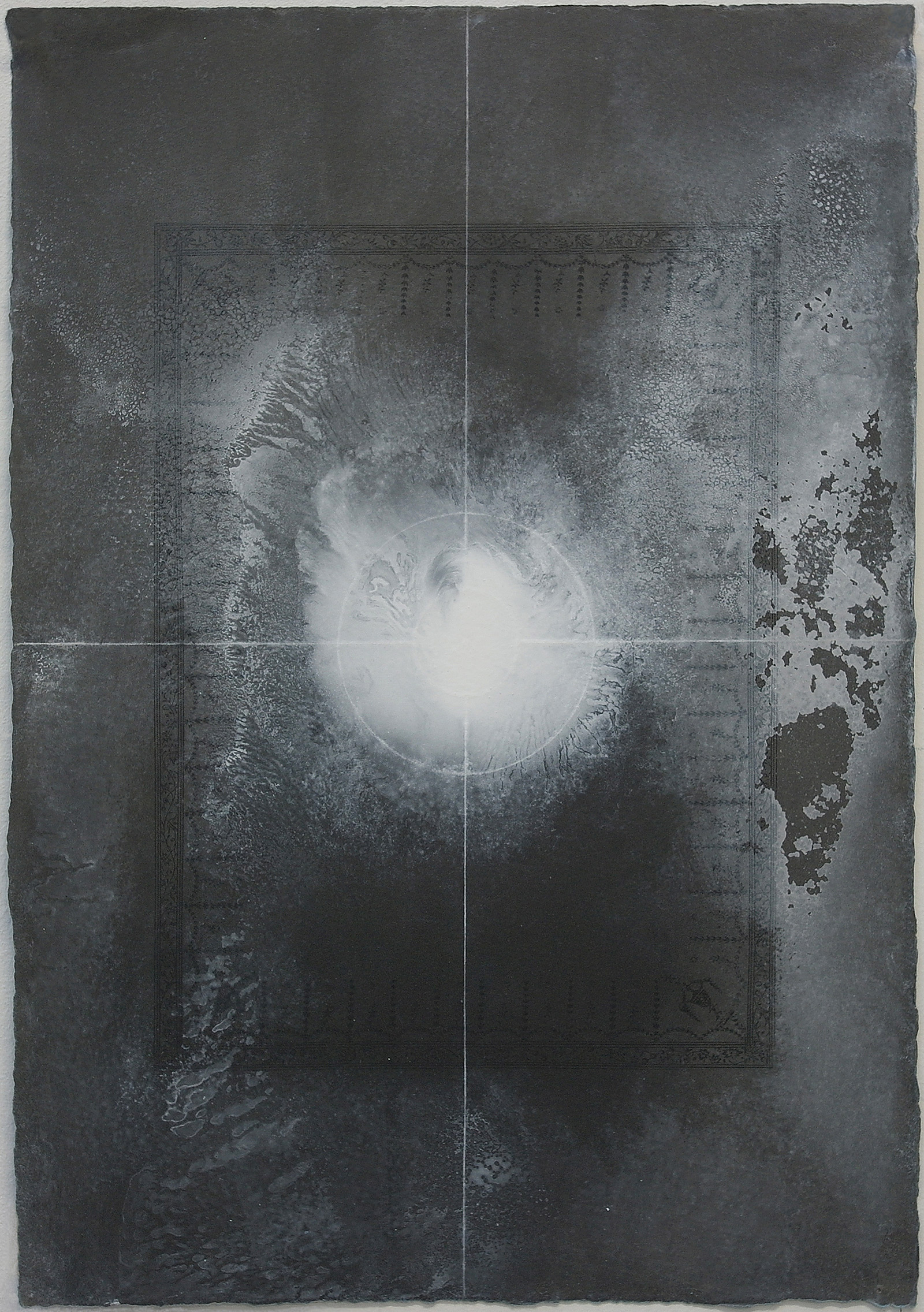

Mary Morrison, of the Isle of Harris, also interrogates the Imperial interventions of the 1800s in her artworks. She questions the role of maps as a means of controlling the Highlands and Islands post Cullloden (1745) through two series of work - both aptly titled ‘Mapping.’ One work from the two-part series is called Seaforth I, referring to the lengthy Seaforth Mackenzie Landowner Regime on Lewis (see image 9). The political ramifications of the Seaforth regime are called into question by the ambiguity of the map to function as a map – the work is better described as abstract art. The fact that Seaforth I is included in a series of titles such as Boundary and Territory suggests this work ‘maps’ out the complexities of land ownership under the Seaforths’ control. It suggests we are still struggling to navigate the longstanding effects. The titles of her work ask who has traditionally set boundaries on the land, whose best interests were considered when dividing it up and selling it and, finally, who had jurisdiction over the land historically. Morrison uses a murky colour scheme, which arguably reflects that the Seaforths often held murky and morally dubious positions abroad as well as at home, such as being governors of Barbados or plantation and slave owners in Guiana. The murkiness also seems suitable in that it reflects the nuanced landowner/ tenant relationship, given that tenants in the 1800s were often at the mercy of how benevolent their landlords were (or weren’t).

Image 9: Mary Morrison, Seaforth I, 2010-15. Mixed Media on Canvas, 30 x 30cm. © Mary Morrison.

Morrison’s series of maps stress that social and political issues are rooted in land and its ownership. In Road, Morrison makes a map of Kyles Scalpay in Harris, a crofting township, (see image 10). Historically, maps made for estate ‘Improvement’ in the 1800s featured attributes which would attract potential landlords as buyers – attributes such as soil quality, field boundaries, what was farmed where, shelter belts, woods, placement of steadings and villages, the alignment of roads and construction of harbours and piers. Given the intention to place sheep upon the land, crofts were not often marked onto imperial maps. If they did feature, they were often mentioned as expendable and inanimate resources.[xi] Meanwhile, Morrison’s canvas Road focuses on a very small portion of Kyles of Scalpay; just the traced outlines of a croft, a few outbuildings, the adjacent fields and the road. She centres the crofter at the heart of the landscape in her re-mapping of Harris. It is the rights and land interests of those who work the land that she is interested in and supports. She subverts mapping conventions of the Imperial maps to instead favour the land rights of crofters.

Image 10: Mary Morrison, Road, 2007-2009. 20 x 20 cm. Oil and collage on card. © Mary Morrison.

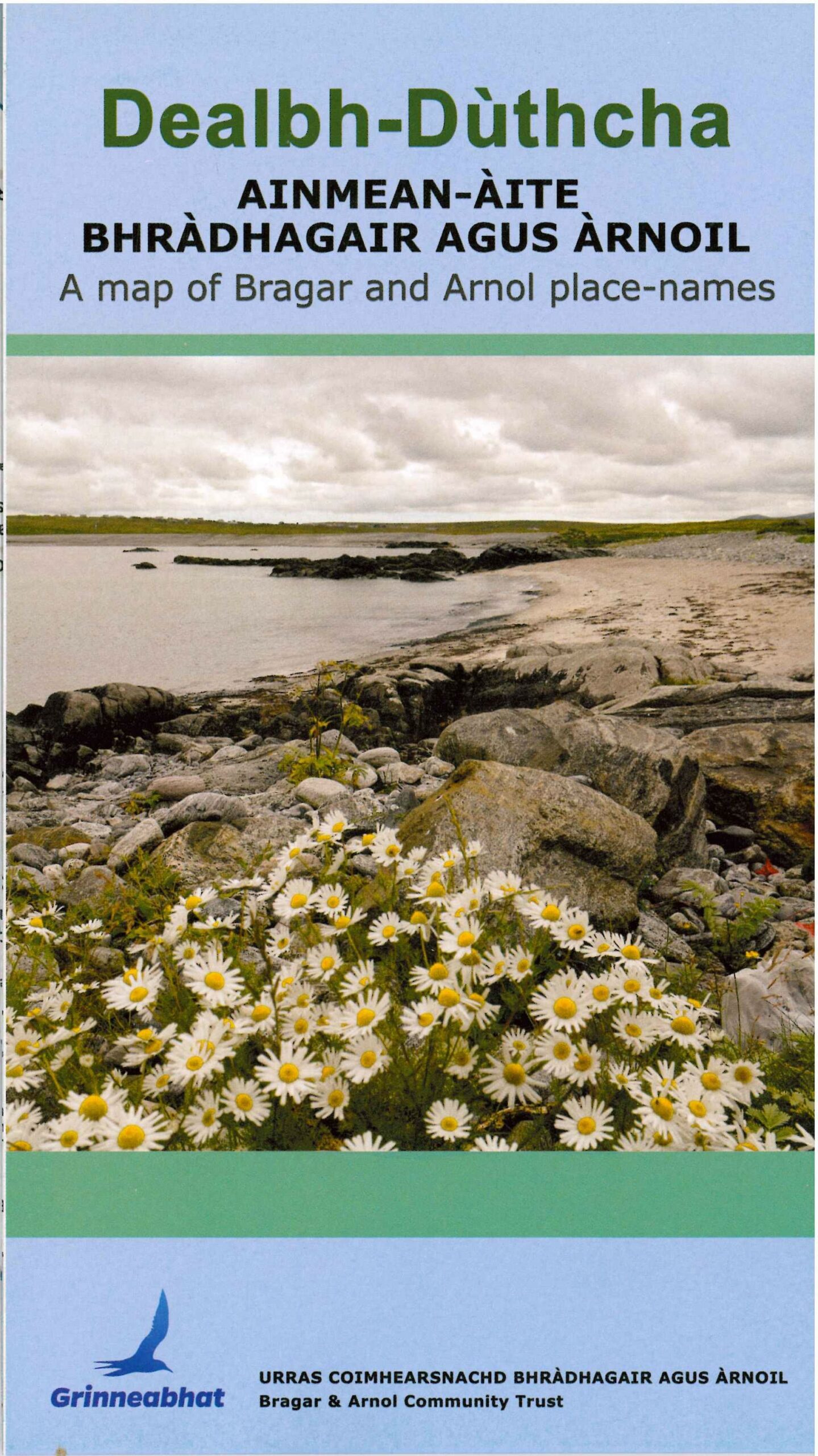

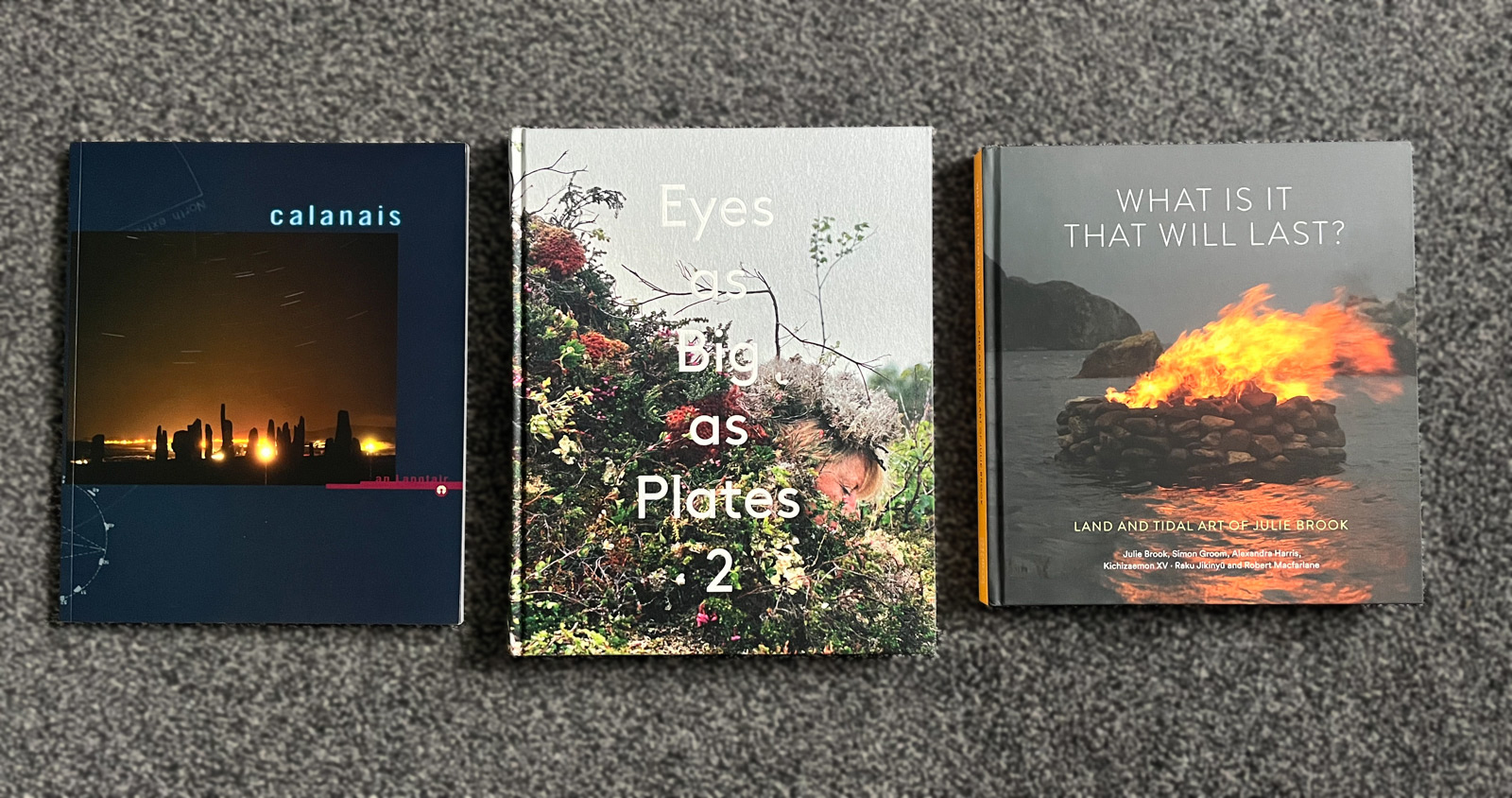

Similarly, re-mapping is a tactic Campbell employs in her work. She utilises re-mapping to honour the cultural history of Lewis. An example of this is her 2017 Dealbh-Dùthcha: Ainmean- Àite Bhràdhagair agus Àrnoil/ A Map of Bragar and Arnol Place-Names. She herself is from the village of Bragar and the mapping process can be seen as an act of pride in the culture of the place she is from. Campbell made the map in reaction to a proposal to build a windfarm on a local peatbog. The peatbog was dubbed a ‘wasteland’ in capitalist terms by the windfarm company. Her response was to create a map which showed the cultural value of the land to the local community. The title of the map reads Dealbh-Dùthcha, which translates as ‘a picture of the land,’ but her word choice was intentional. In the Gàidhealtachd there are many words for land. Dùthcha has connotations of intergenerational connection between certain people in a certain place, ideas of heritage and notions of land being in your blood. Compared to another possibility ‘tìr,’ she specifically chose vocabulary which encapsulates that the land’s value exists entirely in its relation to its inhabitants.

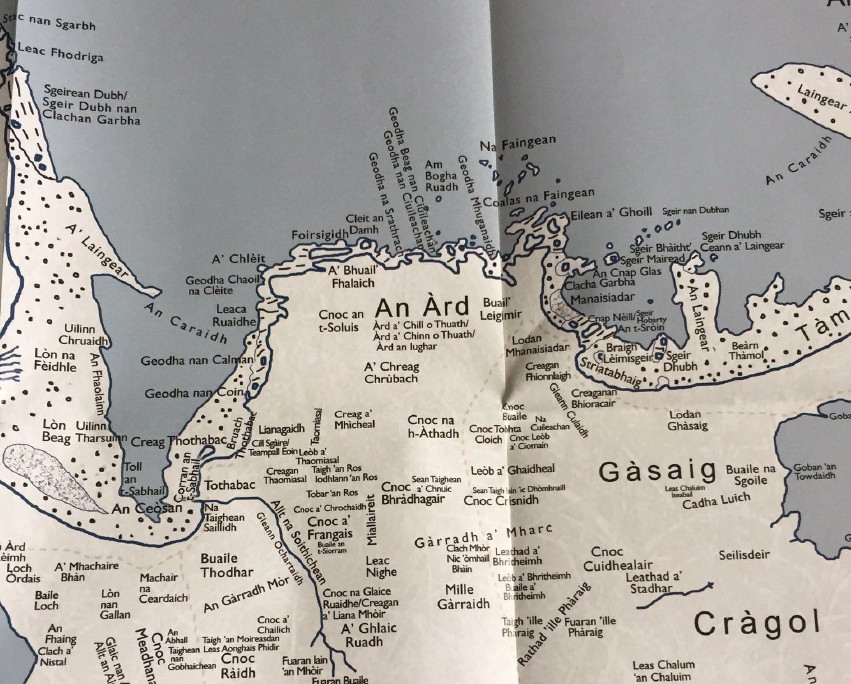

The front cover of her map (see image 11) mimics the style of an Ordinance Survey map layout, which makes a parody of both the spelling mistakes made when they first tried to map out the Highlands and Islands and also what landmarks were deemed worthy of including in the first OS survey maps of the area.[xii] In Campbell’s map, places and names of importance fill the map so the landscape can be read linguistically (as seen in image 12). Each name is loaded with a rich history of stories, legends and anecdotes. For instance, one example out of many, Cnoc na Clàrsaich is translated literally as the ‘hill of the harp’ where An Clàsair dall (Roderick Morrison, the Blind harper) played his harp, the music being heard from as far away as Ness. She explains this in English in the section of the map where one would typically expect to find a key: indicating that the key to navigating the landscape is via the local mental mapping scheme whereby placenames connote geography.[xiii] It also implies how the land should be read through its longstanding cultural value to the locals. Campbell’s map impresses upon the viewer the rich lore contained within place names and the pride she feels for the Gàidhlig mapping scheme.

Image 11: Anne Campbell, Dealbh-Dùthcha: Ainmean- Àite Bhràdhagair agus Àrnoil/ A Map of Bragar and Arnol Place-Names, 2017. Sheet Map, folded. Paper. © Anne Cambell.

Image 12: Detail from Anne Campbell’s map Dealbh-Dùthcha.

Pride is a key theme running through all of the artworks discussed, pride in local culture and values. Anne Campbell, Marnie Keltie, Moira MacLean, Ishbel Murray and Mary Morrison all peeled back the boards sealing the empty blackhouses around the Western Isles. They shone light upon the rich stories of those homes, stories not always mentioned in history books. Especially female and domestic stories, the stories of Sorley MacLean’s giggling girls walking home. The artists then interrogated the Imperial interventions which affected home life in the Islands in the 1800s. Their work re-wrote those histories in their own words, or in the words of esteemed local scholars, and then re-mapped the lands according to local knowledge, spaces that Imperial forces had tried to control through Geography. The Gàidhlig language is venerated and utilised in their work. Re-mapping, re-writing history, celebrating local culture and cultivating the use of the local language – all powerful decolonial acts.[xiv] The artists peeled apart the house, decolonising history as they went, and then populated it once more through the stories they tell in their work. As such, their art is as a celebration of their local landscapes and those who have lived and worked those lands.

By Marie-Claire Cameron

This article is based on a longer version, which provides more in-depth analysis of the artists and their wider oeuvres along with fuller research on the thematical topics touched upon here. The original can found online under the title “‘Un-boarding’ the window through which I saw the West: The Excavating Practices of Anne Campbell, Marnie Keltie, Moira MacLean, Mary Morrison and Ishbel Murray”.

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/84074/

[i] Sorley MacLean was born in Osgaig, on Raasay, in 1911, to his father Malcolm MacLean, (from Raasay but whose family originally came from North Uist) and his mother Christina, (belonging to the Nicolsons of Skye).

[ii] Sorley MacLean, “Hallaig.”

[iii] A note on the Clearances in Raasay: Having purchased the island of Raasay in 1846 using money from slave payouts after his demerara plantation was not financially viable post Abolition, George Rainy as landlord of Raasay evicted some 12 townships and 94 families in favour of cheviot farming (John MacInnes “A Note on Sorley MacLean,” in Dùthchas Nan Gàidheal: Selected Essays of John MacInnes, ed. Michael Newton (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2006), pp. 418-421). The Clearances in Raasay, in particular Suishnish, were amongst the biggest in scale that occurred in Scotland - akin to those in Sutherland in terms of the scale of displacement but, unlike in Sutherland, nowhere was even provided for displaced people to go (Eric Richards, The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2016; 2000), 308.). After Rainy, Raasay was at the mercy of the various landowners which followed and the extent of their predilection for deer shooting (Eric Richards, 369).

[iv] Quote from “About Moira MacLean” on her official artist’s webpage. URL: https://moira-maclean.squarespace.com/about.

[v] Murray in Interview with the writer for Dear Green Bothy Project (22nd July 2021).

[vi] For more information please see, for example, David Alston, Slaves and Highlanders: Silenced Histories of Scotland and the Carribean (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Uni Press, 2021).

[vii] Musician Griogair Labhruidh is due a special thanks here for his considered Gàidhlig translations and the time he gave up willingly to discuss word connotations with this writer in aid of the thesis project.

[viii] Iain Crichton Smith “Shall Gaelic Die?” in Towards the Human, Selected Essays (Loanhead: MacDonald Publishers, 1986), 67.

[ix] For more detailed information on the corporeal violence used to stamp out the use of Gàidhlig in schools and elsewhere under Imperial influence, see Iain MacKinnon “Education and the colonisation of the Gàidhlig mind… 2.” Bella Caledonia, 4th December, 2019. URL: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/12/04/education-and-the-colonisation-of-the-gaidhlig-mind-2/. To understand the damage done by the silencing of mother tongue languages under colonial rule, see Ngũgĩ, wa Thiong’o. Decolonising the Mind: The Political Language in African Literature. Oxford: James Currey, 2005. There is more information on the effect alienation from their mother tongue has had on both artists Ishbel Murray and Marnie Keltie in my full thesis, Marie-Claire Cameron‘Un-boarding’ the window through which I saw the West: The Excavating Practices of Anne Campbell, Marnie Keltie, Moira MacLean, Mary Morrison and Ishbel Murray,” available online.

[x] Kelping was exceedingly profitable by the mid nineteenth century, with Lord MacDonald earning some £20 000 a year from kelping/ potash creation alone in 1849. Workers moved to the Hebrides for employment in the kelp industry. See Richards, 291.

[xi] Finlay Macleod, “Preface” in Togail Tìr/ Marking Time: The Map of the Western Isles ed. Finlay Macleod (Stornoway: Acair Ltd and An Lanntair Gallery, 1989), iii.

[xii] Togail Tìr/ Marking Time: The Map of the Western Isles. Edited by Finlay MacLeod. Stornoway: Acair Ltd and An Lanntair Gallery, 1989.

[xiii] In the map’s re-organising of territorial spacing to present information relaying the themes closest to her community’s heart, islander autonomy and cultural significance of the land etc, Morrison’s work is aligned with Community and Indigenous mapping of the 1990s onwards. For more information see and Joe Bryan, “Walking The Line: Participatory Mapping, Indigenous Rights, and Neolibrealism” in Geoforum 42 no. 1 (2011): 40-50. Also Iain MacKinnon and Liam Campbell “'Isteach chun an Oileáin': Reflections on Community Mapping” in Anthropological Journal of European Cultures 19, no. 2 (2010), 97-108.

[xiv] Whether the Gàidhealtachd can be considered a colony is a hotly debated topic in academia, regardless of your response, though, looking at these artists’ work through a Postcolonial lens is illuminating, given the decolonising trends throughout their work. Decolonising trends that are mirrored in Gàidhlig literature and are well noted in Silke Stroh Uneasy Subjects: Postcolonialism and Scottish Gaelic Poetry. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2011.

Ishbel Murray, Progress, c. 2009. Oil on canvas. © Ishbel Murray.

“Tha bùird is tàirnean air an uinneig trom faca mi an Àird an Iar. The window is nailed and boarded through which I saw the West”. From ‘Hallaig,’ by Somhairle MacGill-Eain (Sorley MacLean). Written in 1952.

Marie-Claire Cameron : 26/Nov/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone

Let me see the bones of things; the organs, the nerves, the sockets, the skin... Alicia Matthews, new work at Grinneabhat.

Article by Andy Laffan : 22/Nov/2025

View Article

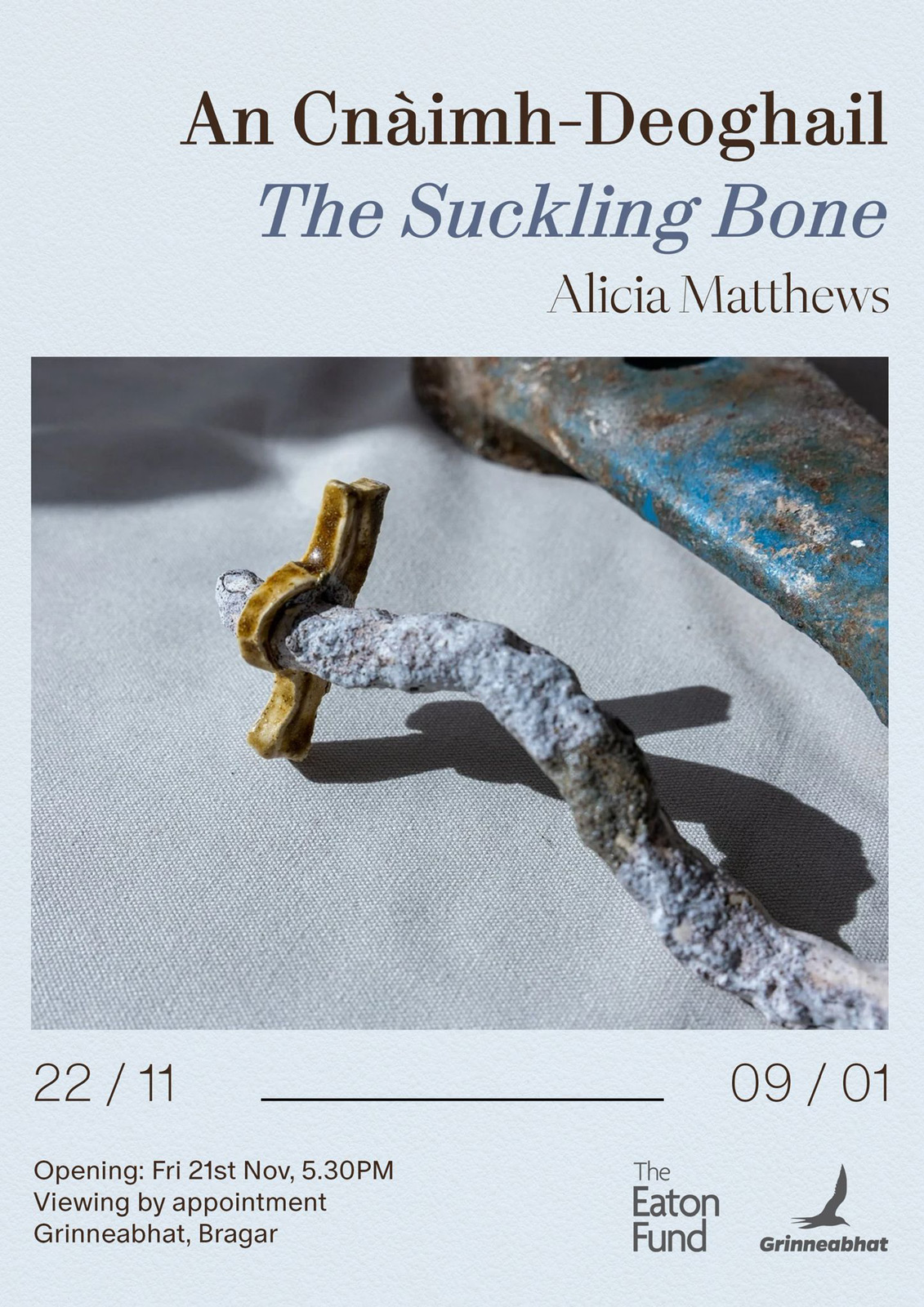

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone

Alicia Matthews

Open: 21st November 2025 to 9th January 2026.

Viewing by Appointment (info@bragararnol.org), Grinneabhat, Bragar, Isle of Lewis.

Let me see the bones of things; the organs, the nerves, the sockets, the skin.

The component parts

that hinge where meaning moves

Let me see them

Let me hold them

I'll demonstrate their use.

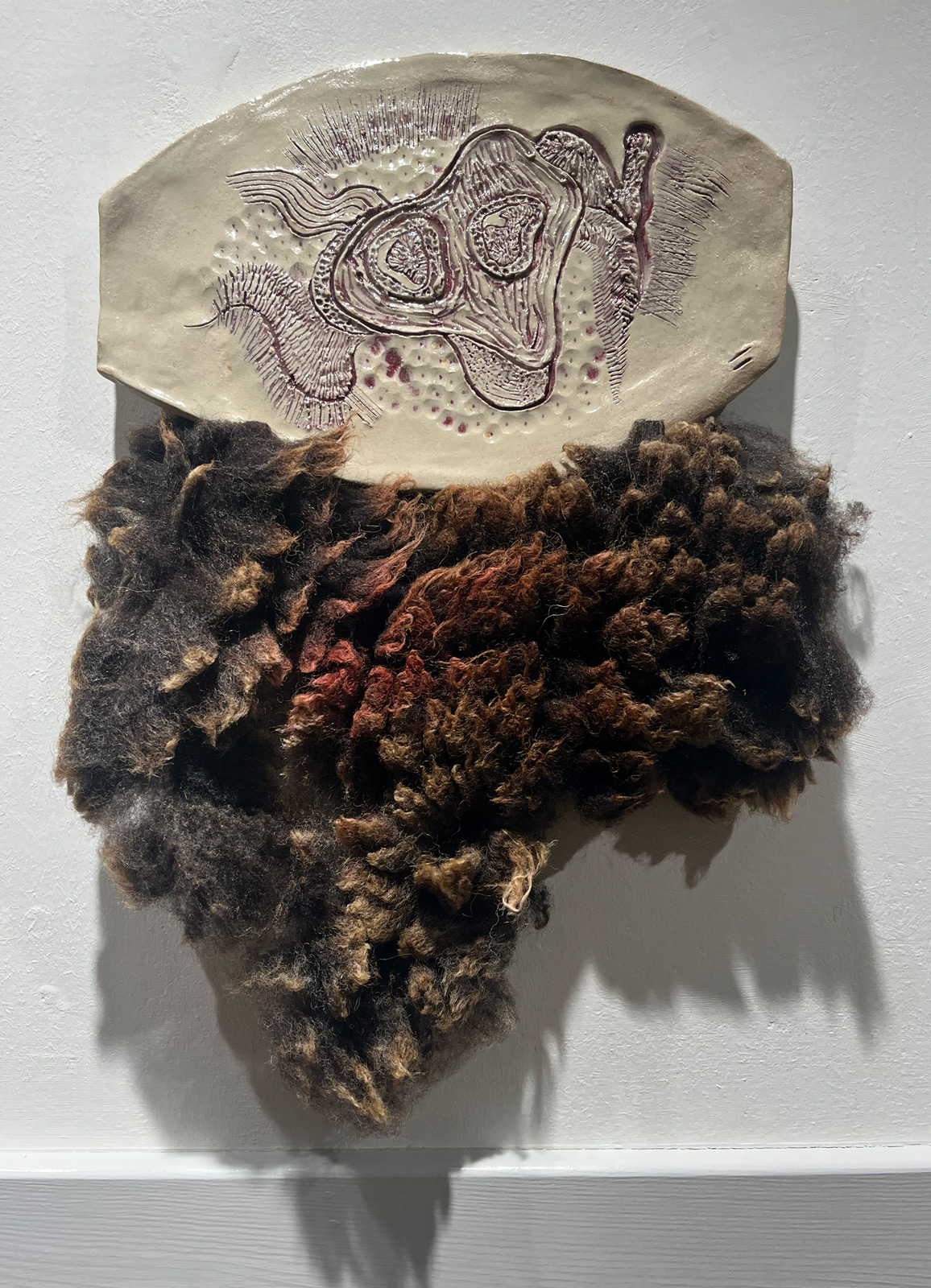

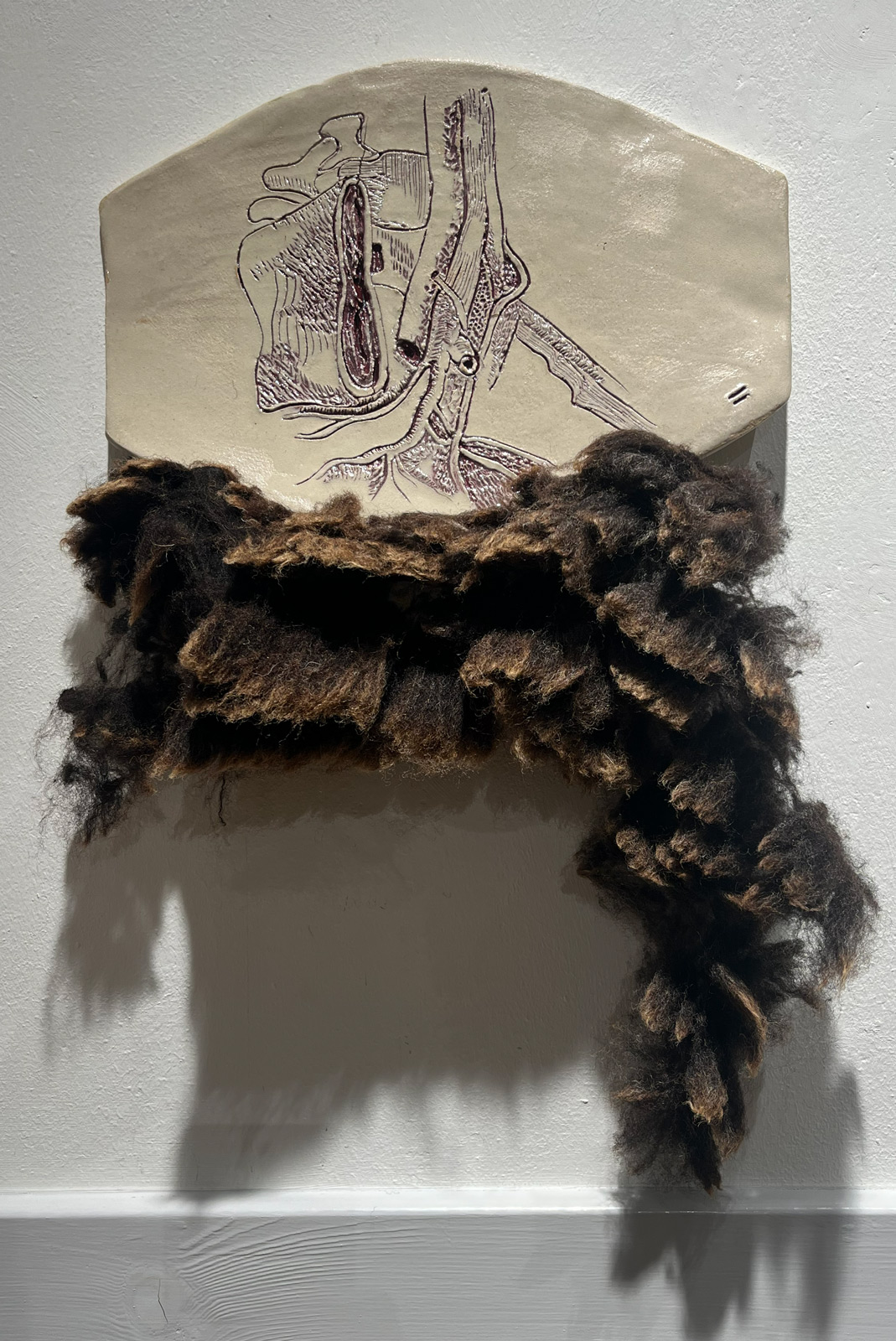

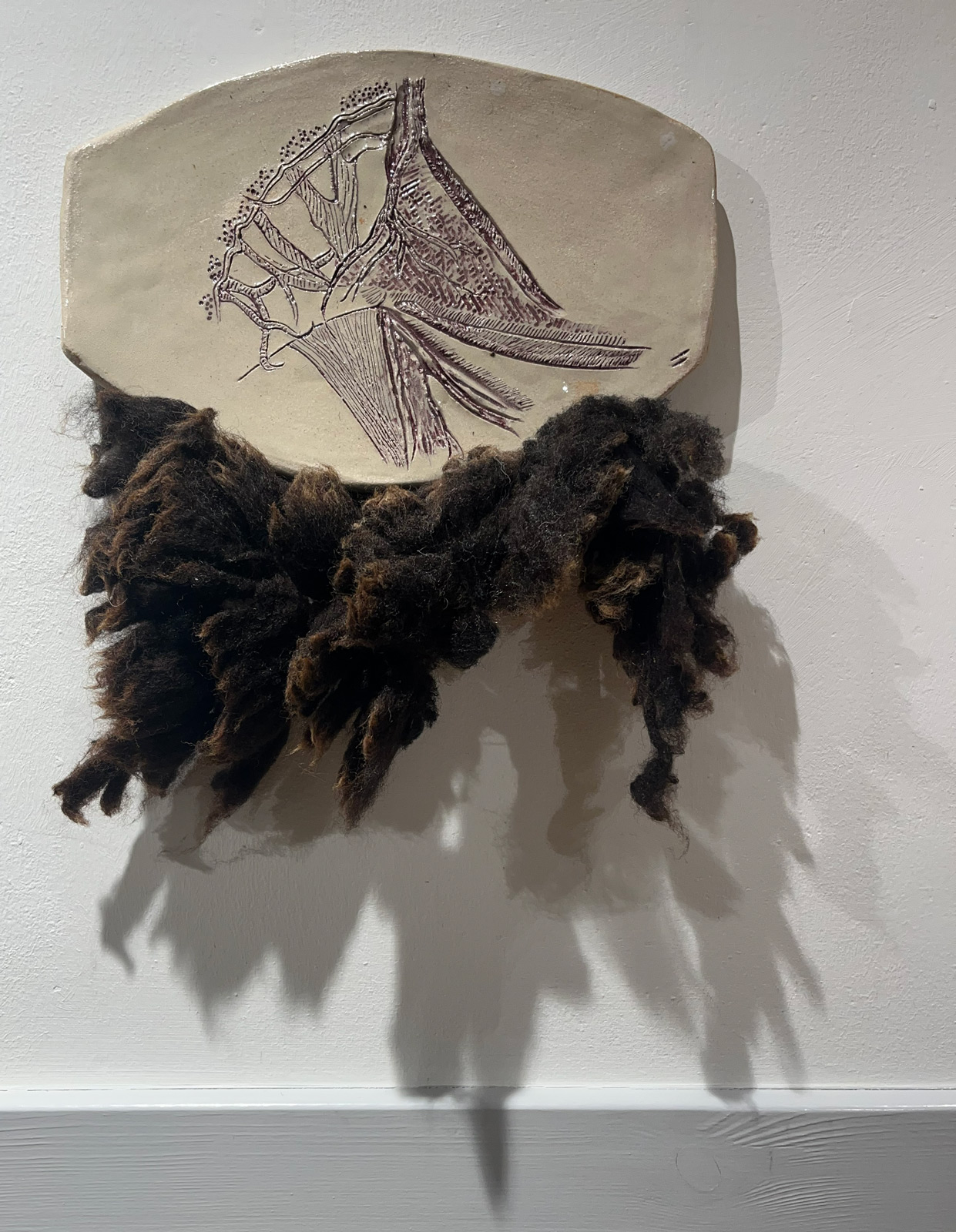

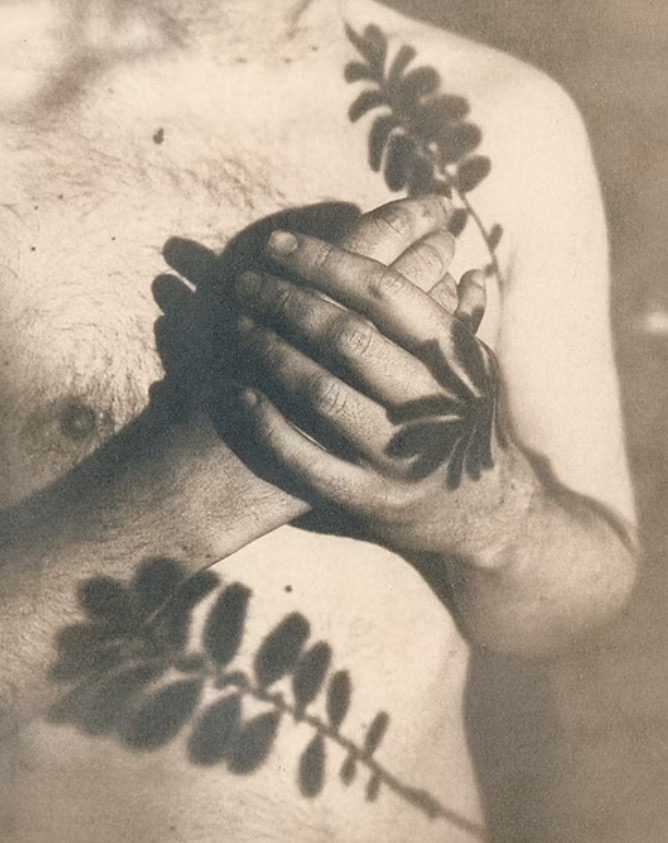

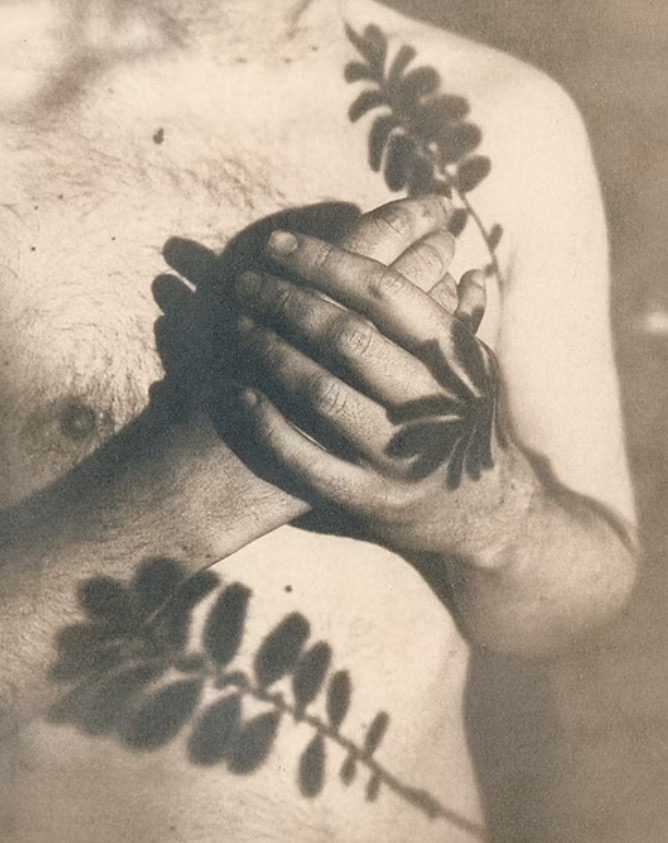

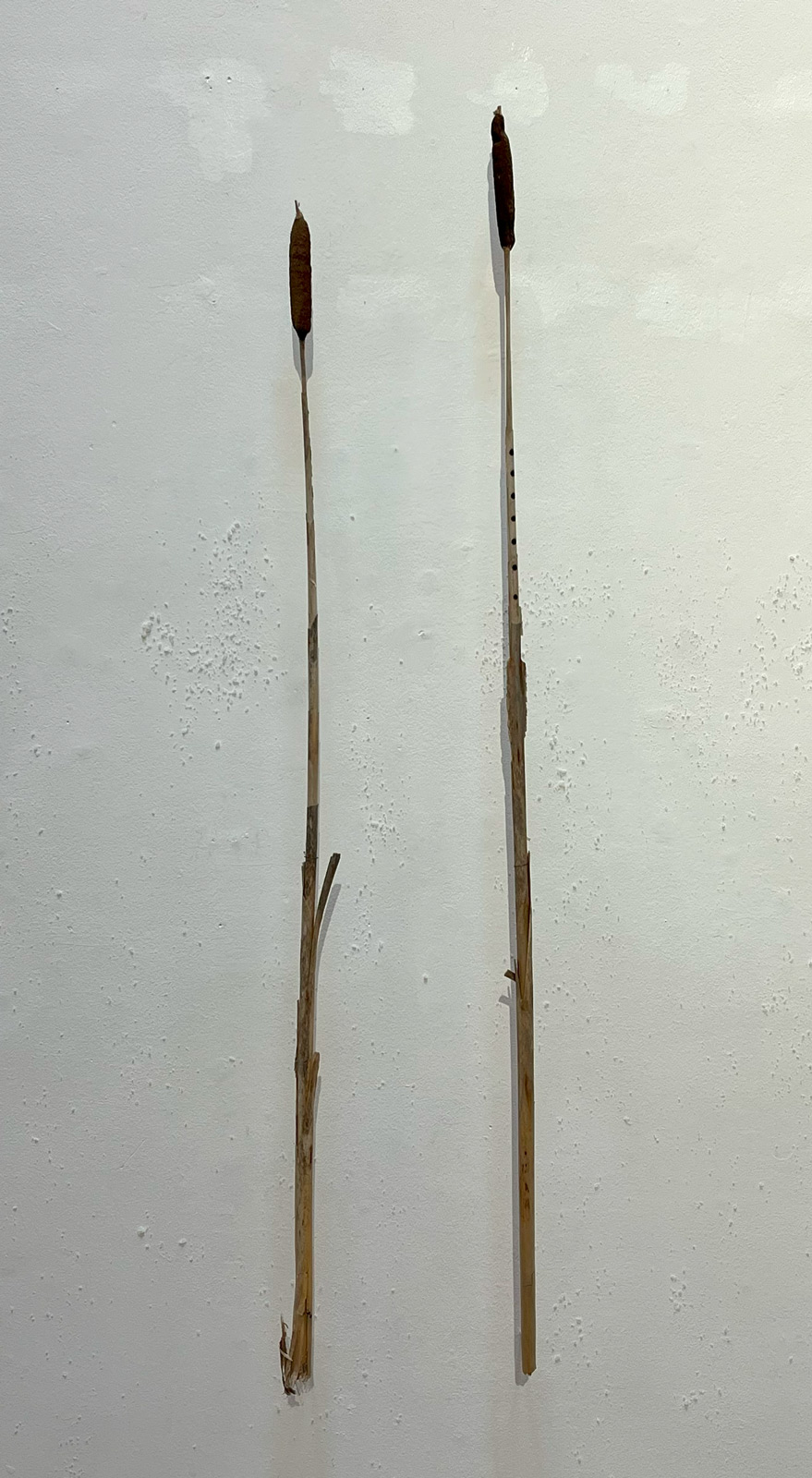

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone brings together motifs of industry with visceral impressions of birth to explore notions of utility in the maternal body and the land.

Experimental ceramic sculptures: umbilical cord snakes, gripped clay birthed, foetal forms, close ups of sockets and cracked pelvic tendons are cradled by rusted engine parts and corroded steel, alongside a series of drawings and textiles.

Materials: Steel, stoneware clay, glazes made from earthenware clay dug from the moor, peat ash, wood ash, breast milk, Lewisian Gneiss, Siabost Quartz and residual sand, sheeps' fleece, red woollen thread, 250gm cold pressed paper, pencil, cotton and nylon silk.

Developed on residency at the Scottish Sculpture Workshop. Supported by The Eaton Fund.

With special thanks to Grinneabhat, Annie Maynard, Lucy Skaer, Robbie Thomson, Nancy Nicolson, Jon Macleod, Anne Campbell, Alex Hackett, Fes Simmonds, Macaulay College, Richard Greenslade, Elly Fletcher, Mike Andrews and Jamie Ellis.

A note from the artist

The bones of this body of work came to me in the early heady post-partum days after the birth of my second child - I was feeling powerful, creative in my maternal body and totally exhausted.

There was a pile of rusted and discarded tractor engine parts sitting by the shed door that was previously largely ignored. Now the cogs and pipes and other parts I cannot name kept catching my eye when heading out for peats. They, in all their steely industriousness, felt visceral soaked in their rust.

This show merges together several ideas that centre around the body. Mostly my body. I limped around in the weeks after the birth, as my pelvis started to knit back together, and I felt akin to this pile of rusting cogs. This phrase, inadvertent vessels, kept coming to mind as I looked at these cold industrial objects and envisioned them containing soft warm ones.

The materiality of this work is important to me. Working with my hands; with clay and with needles and thread seems to emulate the practicality of mothering. Entering the gallery, the scent of lanolin and milk greets the viewer. Smells which I feel sort of ground it in the place. The idea that these cast metal objects were at one point liquid too, the earthiness of the clay and the wee clinks of ceramic on metal nodding at their fragility but also in a quiet toast.

The title of this work comes from a phrase, that I believe is, from Harris: an càimh deoghail. I came across it as I was searching through Am Faclair Beag for words and ideas pertaining to bones. It told me it meant pacifier - a bone given to children to soothe. I was told my good friend would suck out the bone marrow from a bone when they were tiny too. It seems to me, a good phrase that encapsulates this sense I want to portray of the body rooted in and of the landscapes we exist within. The nourishment it provides us, the nourishers.

Exhibition Poster, 22/11/2025 to 09/01/2026

Alicia Matthews is an artist and audio maker living and working in the Outer Hebrides.

https://www.aliciamatthews.co.uk/

Past projects have used moving image, performance, sculpture and sound to explore technological hauntings, societal glitches, common land, geology and deep time - often as speculative fictions. Recent work uses haptics, text, drawing and ceramics to investigate the maternal body, witches, The Gaelic Otherworld and relationships between rusting detritus and blanketing bog.

Previous work has been exhibited and performed across the UK - including at Glasgow Tramway, Camden Arts Centre, Tate Modern and Tate Britain - as well as internationally at galleries and festivals in Lublin, Venice, Guangzhou and New York. Alicia holds an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art and an MSc in Sound Design and Audio-Visual Practice from Glasgow University.

Past compositions have been commissioned by platforms including Jerwood Resonance, Present Futures and Radiophrenia.

Musical projects include Malaizy (Few Crackles), SUE ZUKI (Domestic Exile), LAPS (DFA records, MIC records) and Organs of Love (Optimo Music). Alicia co-runs the independent record label Domestic Exile and hosts a long-standing monthly show on NTS radio.

In October 2025, Alicia & Robbie Thomson founded HAAR Projects, an arts organisation focussing on the production of ambitious visual and sonic art projects that engage communities across the Western Isles.

An Cnàimh-Deoghail / The Suckling Bone

Let me see the bones of things; the organs, the nerves, the sockets, the skin... Alicia Matthews, new work at Grinneabhat.

Text from exhibitions notes.

Article by Andy Laffan : 22/Nov/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian, Jake Harvey RSA and Helen Douglas.

Mike Donald visits An Lanntair to review the latest exhibition from Jake Harvey and Helen Douglas, Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian.

Article by Mike Donald : 30/Oct/2025

View Article

Archaen Fold II, Jake Harvey, Lewisian Gneiss.

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian, Jake Harvey RSA and Helen Douglas.

Review: Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian

An Lanntair, Stornoway

18 October – 29 November

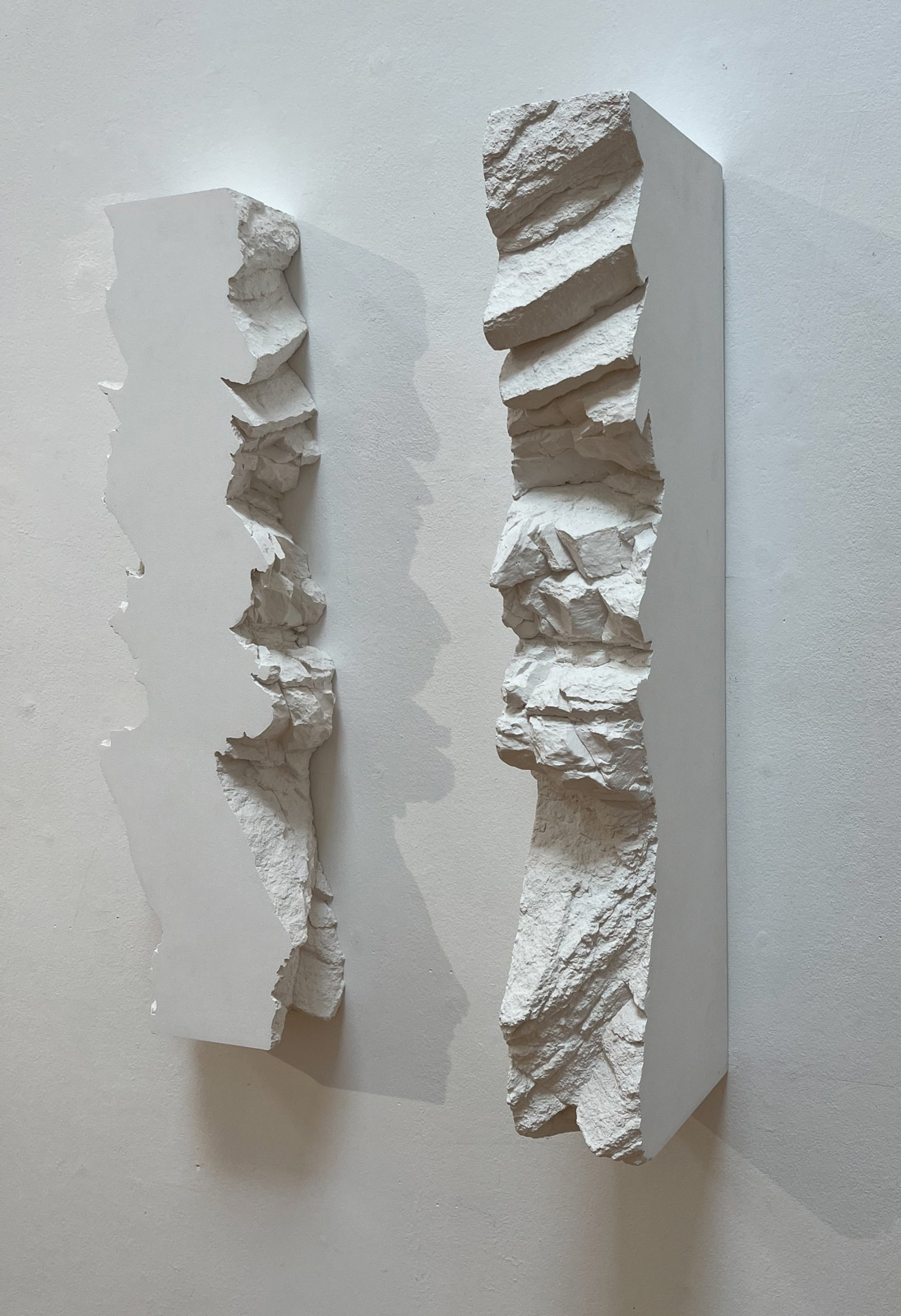

Three billion years before stories were told of these islands, before peat, people and crofting, there was rock: pressed, folded, twisted. The Lewisian Gneiss Complex forms the ancient bedrock of our Outer Hebridean archipelago. We see it everywhere, as island roads have long since carved their way through its pretty patterns, revealing what normally lies hidden beneath our feet.

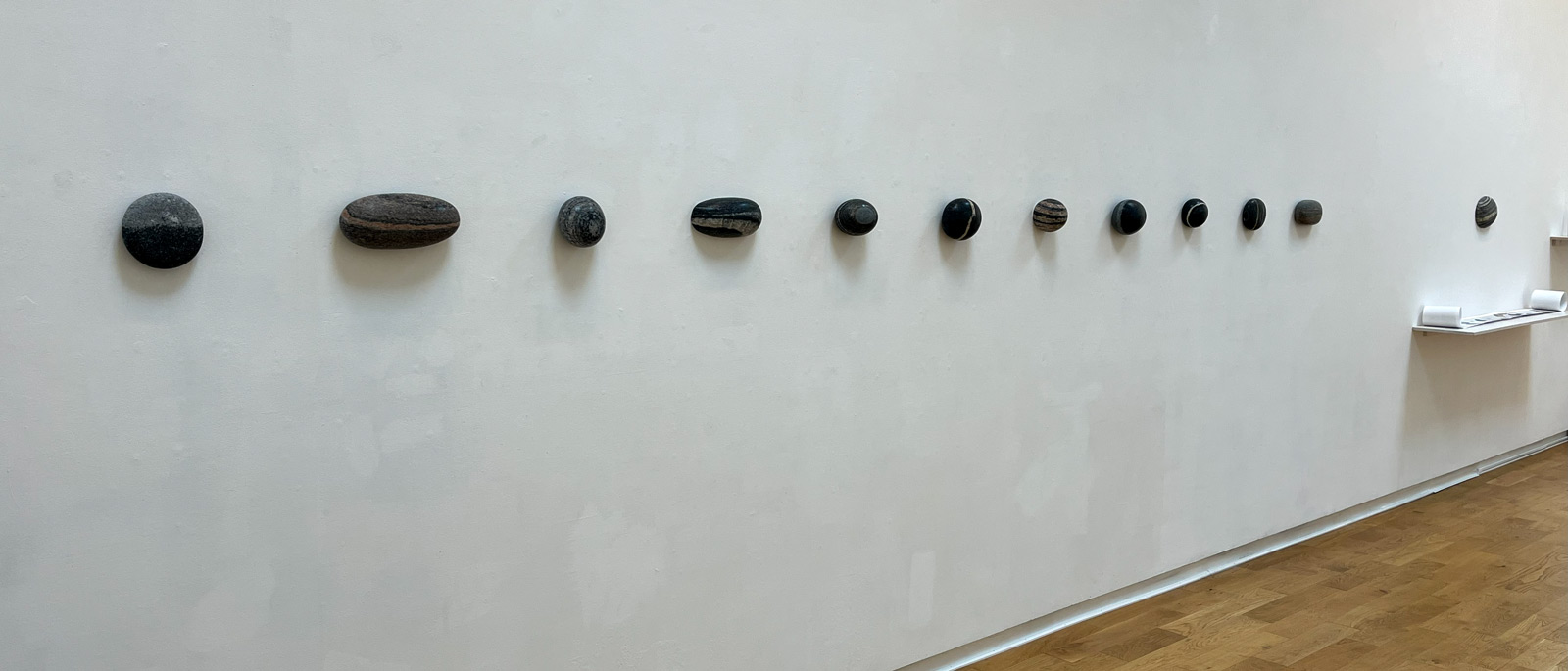

Jake Harvey: No Vestige of a Beginning / No Prospect of an End - Stones 1 to 15.

Lewisian Gneiss / Cathness Slate.

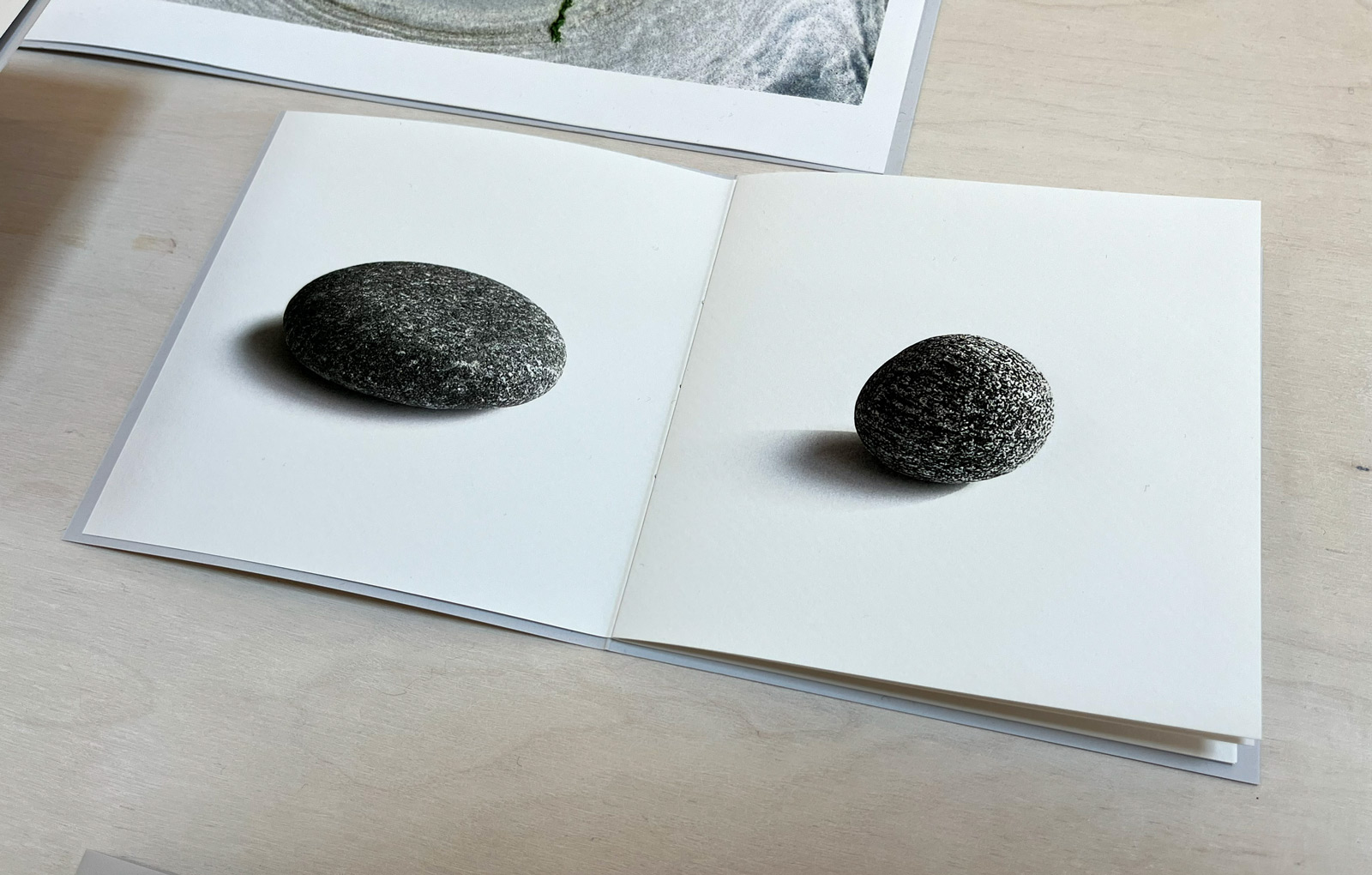

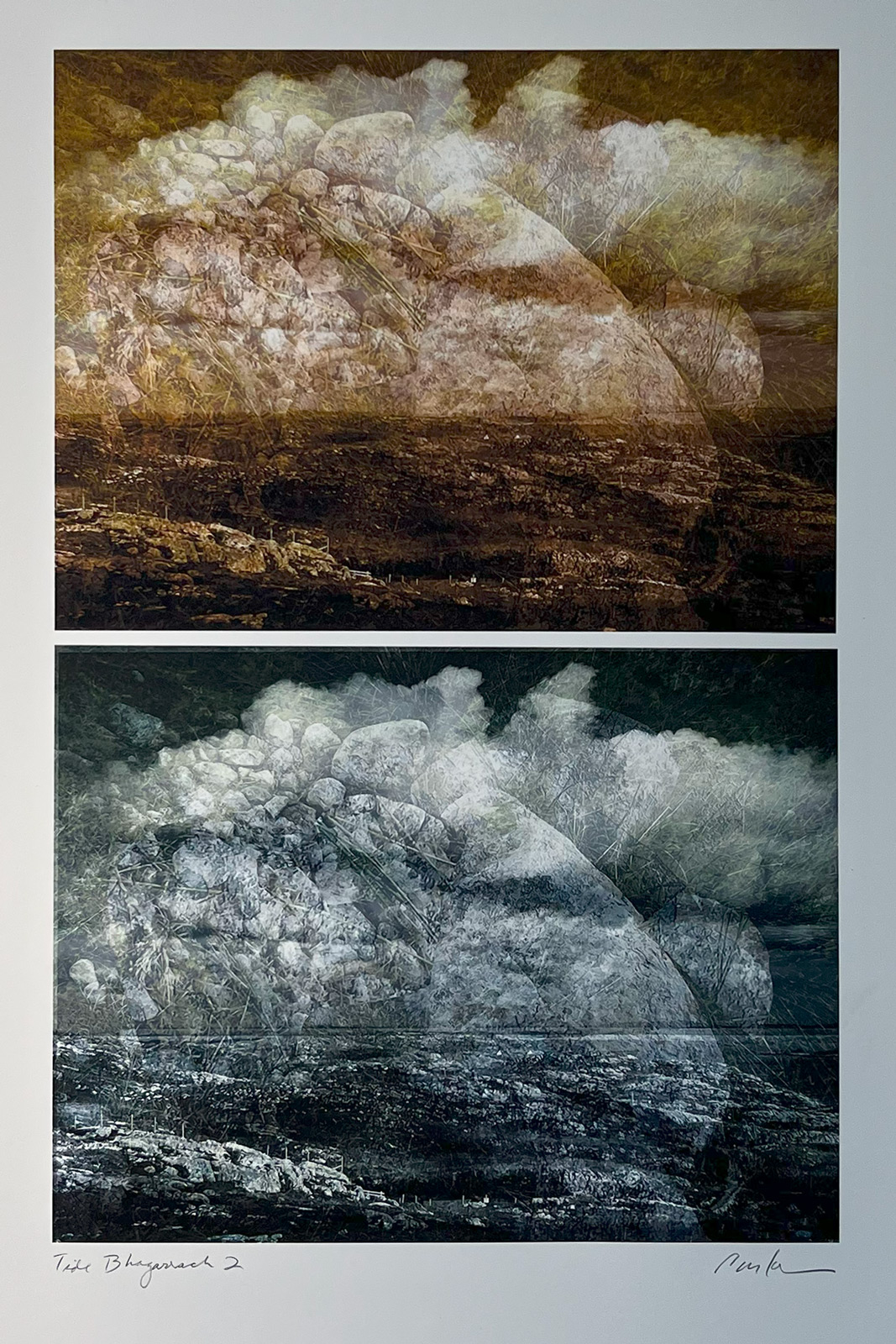

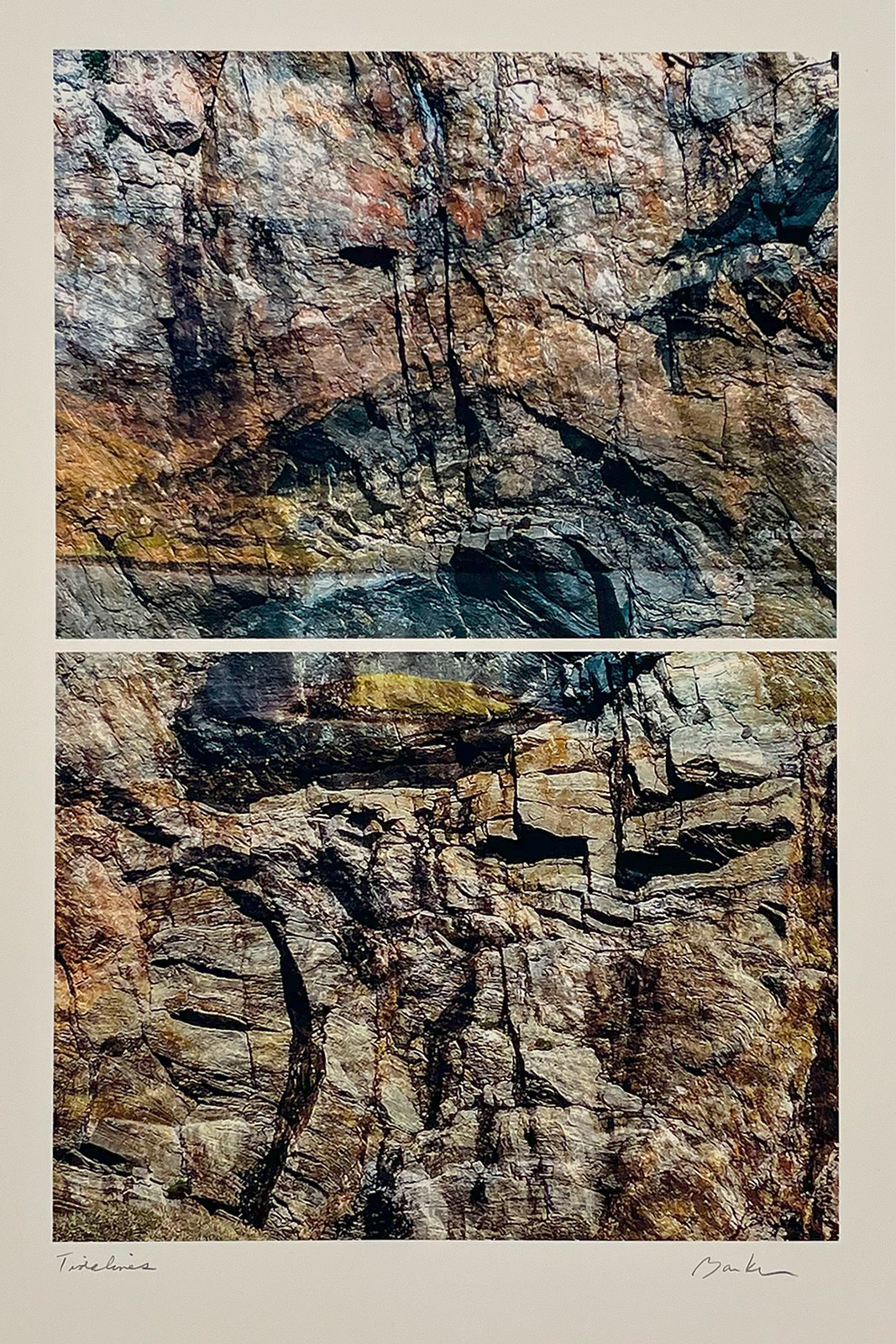

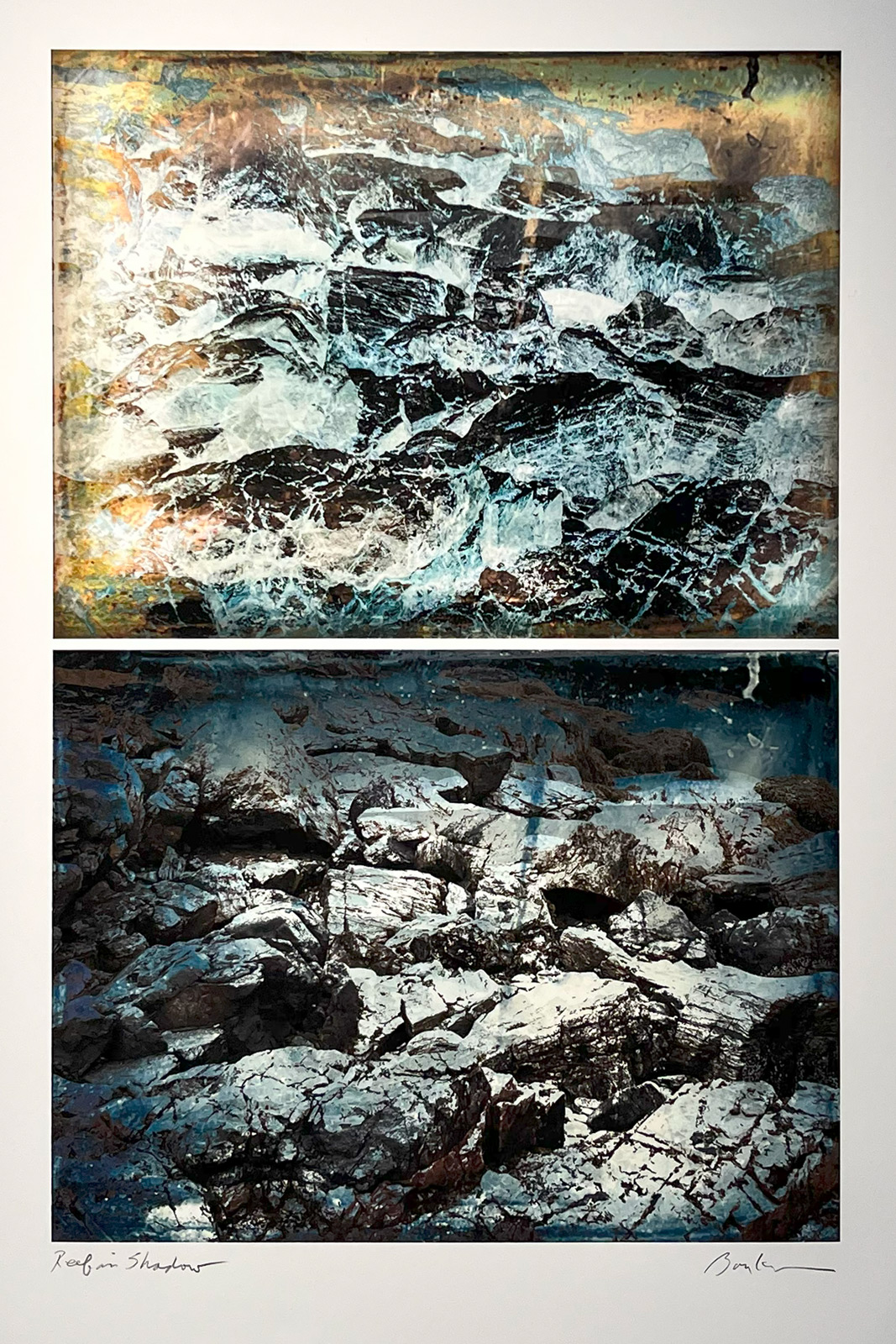

In Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian, sculptor Jake Harvey RSA and book-artist Helen Douglas respond to this foundation not as something static, but as a living archive of experience. Inspired in part by the early geological thinking and work of Scottish geologist James Hutton, their artworks explore stone as both material and memory, a medium shaped by forces older than life itself.

Helen Douglas: STONE 4

From a set of 5 books, hand stitched, printed edition of 100.

Harvey’s contribution comprises a series of sculptures carved predominantly from Uist stones. His forms evoke weight and history. Some lozenge-like pieces hint at unfinished or unknown architectural purposes. Others suggest imperfect cannonballs from a long-forgotten Outer Hebridean battle. The larger works have an almost animalistic presence. One piece, Boundary, lazes on a copper coloured plinth like a fat, limbless grey seal hauled out on a rusting rock.

Jake Harvey: Lewisian Stratum. 2025.

Lewisian gneiss and corten steel.

Swirls, stripes and mineral seams dance across shiny surfaces helping to reveal how violently these rocks were once transformed. But, there is a playful ambiguity in these objects that invites the imagination to wander. Several look like dinosaur eggs. Others have the weight and scale of prehistoric curling stones. The vitrine table of smaller pieces under glass suggests Neolithic tools, all polished ideas of chisels, ancient die, or paperweights long before paper existed. The effect is quietly anthropological and awe-inspiring all at once.

Jake Harvey: Minatures Vitrine, 32 minatures.

Lewisian gneiss, marble, limestone, granite, metadolerite.

Polished stone craft is well familiar to these islands however. We have all seen jewellery and trinkets made from the endless supply of rocks at our feet. So, Harvey’s work is most compelling when he moves beyond smooth finish into deliberate artistic interventions. Intricate sculpting techniques and subtle paints produce bright ovoids and flowing lines of colour carved among natural marks and textures in distinctly human ways. These now feel like small rosetta stones of long-lost island languages.

Jake Harvey: Two Ovoids, 2025.

Basalt and enamel paint.

Jake Harvey: Six Lines, 2025.

Basalt and enamel paint.

Jake Harvey: Basalt Flow II, 2025.

Basalt and enamel paint.

Helen Douglas approaches the same material from a different point of entry. Through photographic bookworks, concertina structures, folded pamphlets and scroll-like pages she renders geology as a time-based reading experience. Some works sit on plinths that leave the viewer unsure whether they can be touched or read, or if they are simply to be observed. The long scrolls display the flowing geological imagery beautifully, while the fans feel just a little more incongruent.

Helen Douglas, Dune, 2025.

Leporello fan, inkjet print on Munken paper, card cover, hand stitched, edition of 20.

Helen Douglas, Lewisian I, 2024.

Handscroll. Giclee print on Munken, 30cm x 4.5 metres, edition of 4.

Overall, Meeting Point feels entirely of this place. When Douglas’s formats and imagery align with Jake’s work, there is an overriding sense of beauty in these, the most grey of our ancient rocks. And, importantly, there is movement too: long-frozen tides, shifting strata and moments unfolding not in centuries but in epochs. It does not romanticise the landscape. Instead, it listens to it. The result is a thoughtful, calm and tactile encounter with the oldest story these islands hold, one still unfolding as time and tides continue to take their toll.

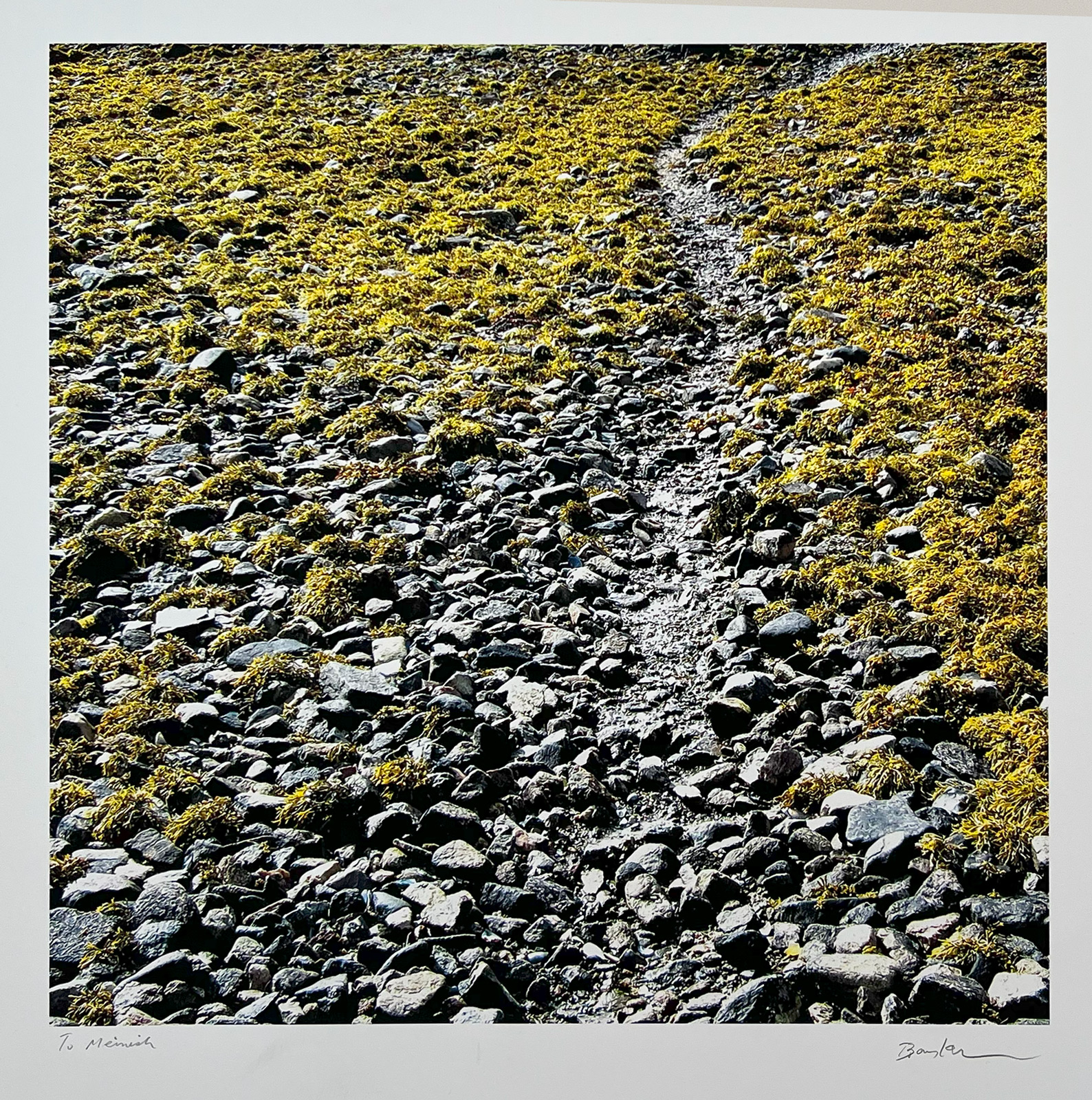

Jake Harvey: Raised Beach, 2025.

Five metres of Lewisian gneiss and metadolerite.

Jake Harvey and Helen Douglas: Meeting Point Within the Lewisian.

Mike Donald - Off The Croft Stories

Off The Croft Stories sets out to explore the Outer Hebrides through a contemporary lens, cutting through the clichéd clouds of peat smoke and picture perfect postcards.

https://offthecroft.substack.com/

Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian

Exhibition open 12 July - 23 August 2025

An Lanntair, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis.

Exhibition book available from Taigh Chearsabhagh

Jake Harvey RSA

A life-long experience of living and working in Scotland, and the meditative aspect of fishing inform Jake Harvey RSA’s approach to sculpture at a profound level. Extensive visits to museums, archaeological and architectural sites around the world to record the traces of humans through drawing and photography, are the information-gathering process and primary touchstones for his practice.

Jake Harvey RSA: ‘The sculptures I make evolve from things seen, experienced or imagined. Some develop from drawing or as tangents from works previously made. Some simply emerge from the experience of working with material and the making process. I work with predominantly earth-related materials and currently mainly with stone, the matrix of our planet. Stone's geological formation, erosion and deposition and how it has created the landscape over millennia and how man has utilised stone is significant; as are the archaeological traces, monuments and tools that evidence that evolution.

'In drawing and sculpture, I aim for an art of simplicity and essence and often focus on the interdependence of form(s) and negative spaces (both enclosed and peripheral). ‘

Source: RSA https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/artists/321-jake-harvey-rsa/overview/

Helen Douglas

Helen Douglas is a Scottish book artist, publisher and educator known for her work with artist's books.

Douglas was born in Galashiels, grew up on a farm in the Scottish Borders, and studied at the Carlisle College of Art and Design. She received a BA in History of Art and Architecture from the University of East Anglia in 1973 and pursued post-graduate studies in textile design at the Scottish College of Textiles. In 1975, Douglas settled in Yarrow. She received a PhD from the Arts faculty at the University of Edinburgh in 1997.

From 1975 to 1994, she produced artist's books under the series name Weproductions in partnership with Telfer Stokes; since then, she has produced her books solo. In 2006, Douglas was made a life member of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Douglas has lectured at the Scottish College of Textiles, was a lecturer on book arts at the University of the Arts London, and has been part of a research group investigating the artist's book in digital format.

Curator and Librarian Clive Phillpot writes, "Helen Douglas has been engaged with nature and with narratives for much of her life. Her formative years were spent in the Scottish Borders in a farming community, and she returned to live there as a working artist. Her chosen medium for embodying her expressive visual narratives has for many years been the photographic image used in conjunction with the book. Her works have been collected and exhibited nationally and internationally, and her achievements in the field of artist books are manifold."

Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_Douglas_(book_artist)

Archaen Fold II, Jake Harvey, Lewisian Gneiss.

Mike Donald visits An Lanntair to review the latest exhibition from Jake Harvey and Helen Douglas, Meeting Point: Within the Lewisian.

Article by Mike Donald : 30/Oct/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

Luchd-Ealain San Fhàsach (Artists in the Wild)

A new film by Ishbel Murray and Ruaridh Urpeth. Artists Anne Campbell, David Greenall, Laura Maynard, Margaret Stevenson, Mary Morrison and Rupachitta Roberstson talk of their island studio life.

Article by Andy Laffan : 30/Oct/2025

View Article

Mary Morrison talks about the importance of funding for remote island artists.

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

Luchd-Ealain San Fhàsach (Artists in the Wild)

Luchd-Ealain San Fhàsach (Artists in the Wild)

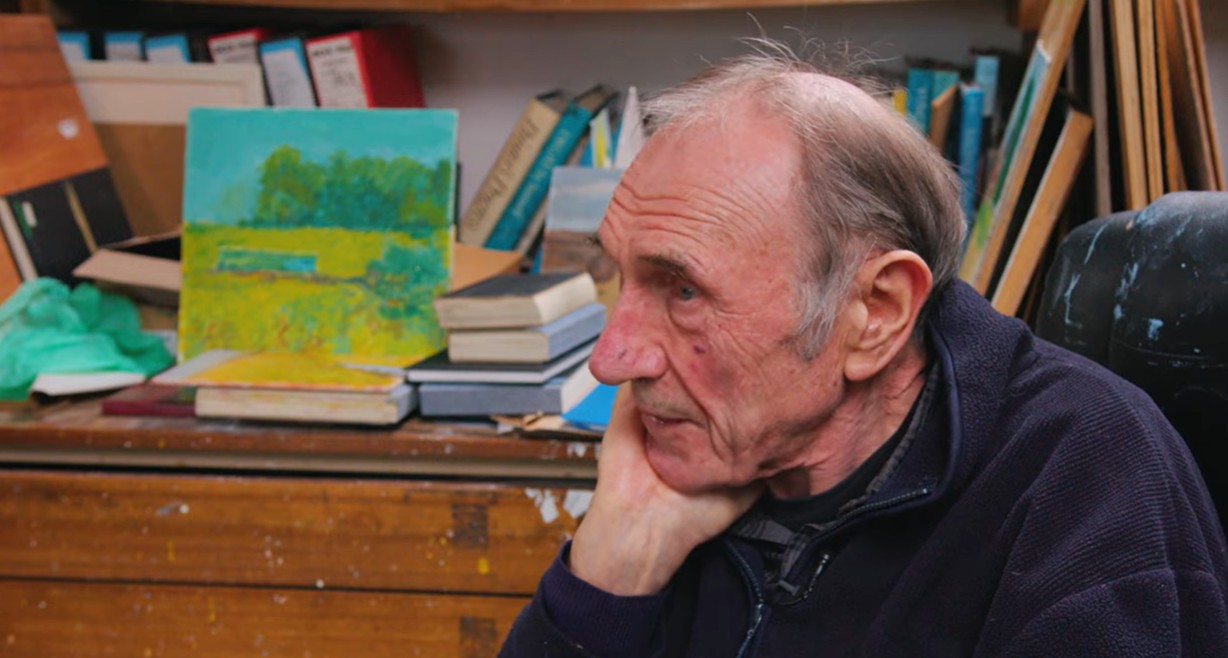

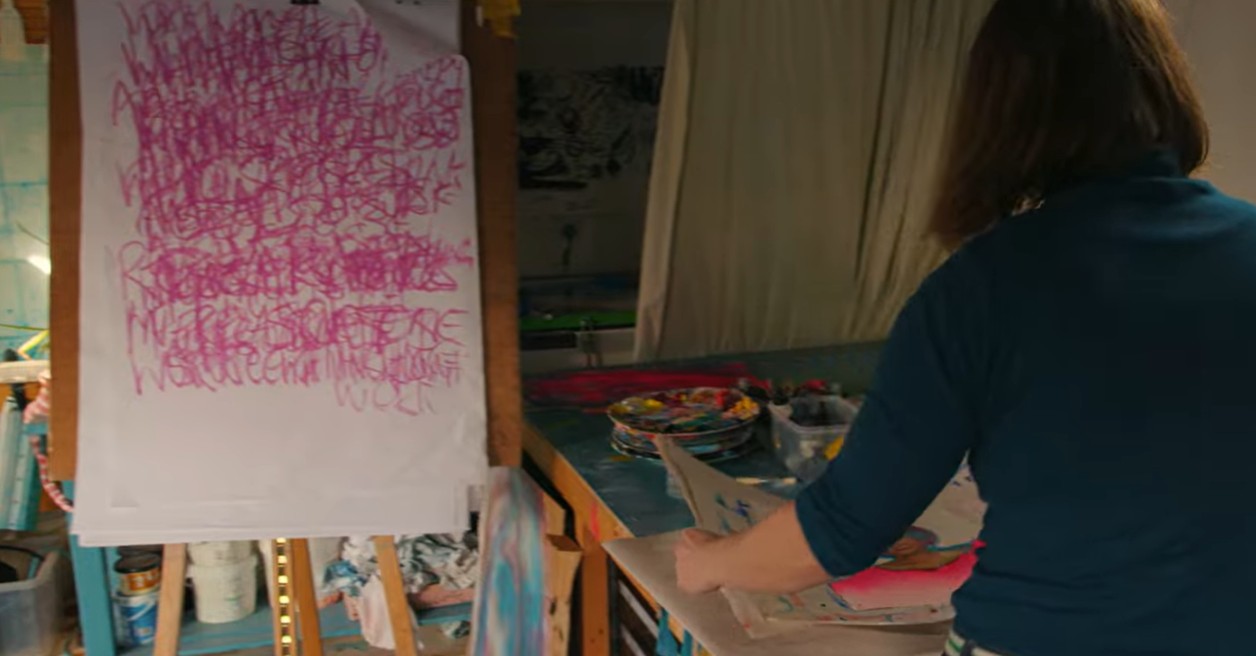

A 'Culture Collective' Creative Scotland funded project that was commissioned in the summer of 2024 by An Lanntair to introduce participants to island based artists. The project allowed participants to visit different artists across Lewis and Harris and to learn about the work and motivations of each of the artists. Each session included an opportunity for artists to take a group out into the landscape that inspires their own work and to encourage them to engage in a creative visual arts activity. Following the project a short film was made to find out more about each artist's creative practice and to get their thoughts on the possible advantages but also the challenges they face as island based artists.

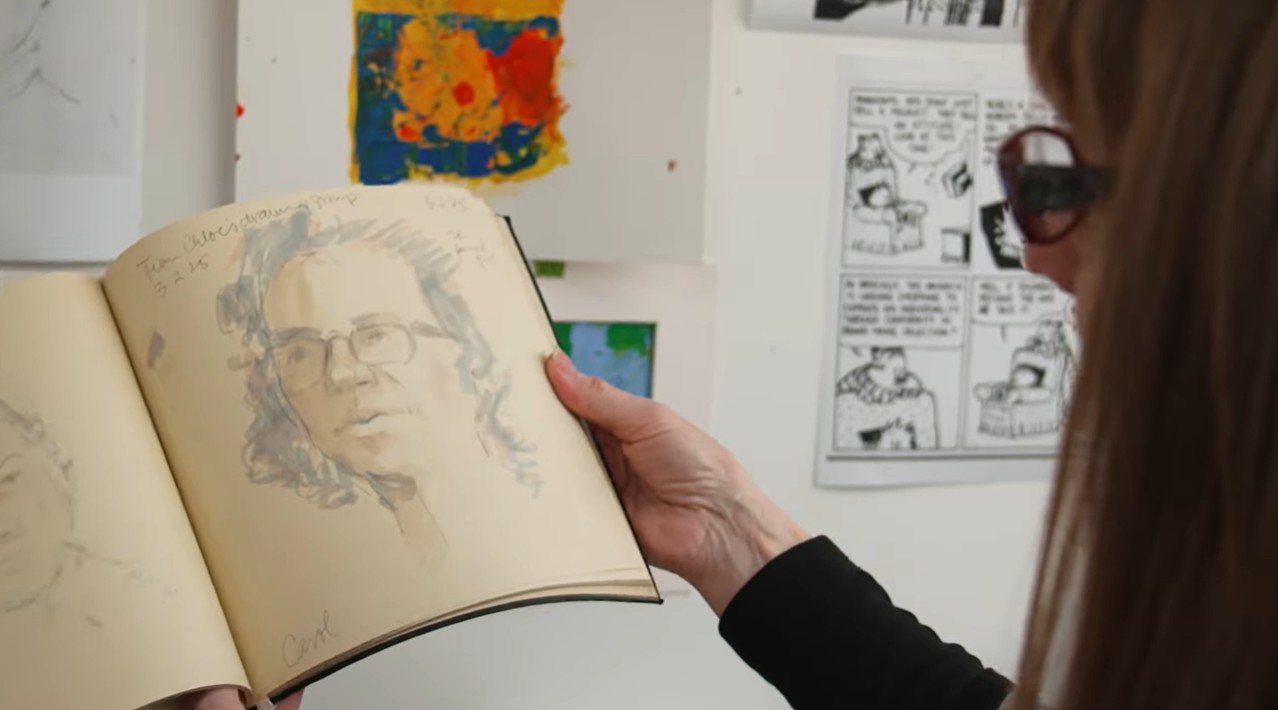

From the interview with Rupachitta Robertson in her studio where she talks of the ‘…special community’

David Greenall in his studio, contemplates his confidence to paint.

Laura Maynard highlights issues of lack of access to facilities and space.

Margaret Stevenson sketches everyday.

Anne Campbell considers the merits of having her own personal space over shared artist spaces.

Ishbel Murray would like to thank Ruaraidh Urpeth for his work in filming and editing 'Luchd-Ealain San Fhàsach' as well as all the artists who took part.

More about the Culture Collective project

Mary Morrison talks about the importance of funding for remote island artists.

A new film by Ishbel Murray and Ruaridh Urpeth. Artists Anne Campbell, David Greenall, Laura Maynard, Margaret Stevenson, Mary Morrison and Rupachitta Roberstson talk of their island studio life.

Content and images sourced from Ishbel Murray's website.

Article by Andy Laffan : 30/Oct/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

Will Maclean: At the Heart of Highland Art

Will Maclean's importance in the development of Highland (and Island) visual art cannot be overlooked. An artist whose work is a must for the Hulabhaig collection (eventually), but for now, I'm deligh...

Essay by Murdo Macdonald : 29/Aug/2025

View Article

Will Maclean and Voyage of the Anchorites. Image credit: Scottish Parliament Art Collection.

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

Will Maclean: At the Heart of Highland Art

Highland art is one of the key strands of Scottish art. That is true if you look back to the time of the Book of Kells being created on Iona in about the year 800, or to the birth of modern painting in Scotland with the Gaelic-speaking artist William McTaggart in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is McTaggart in particular who can illuminate themes that are crucial to Will Maclean’s work – history, land use, and communities – for Maclean and McTaggart share a Highland background and an understanding of Highland issues. My first illumination of Maclean via McTaggart is McTaggart’s painting from 1890, The Preaching of Saint Columba, a wonderful work in the City Art Centre collection in Edinburgh. McTaggart’s work is a strong reminder of the cultural continuity of the Scottish and Irish Gaihealtachd. With respect to Saint Columba those connections usually focus on Iona, but also of great importance was Columba’s first landing place in Scotland, in William McTaggart’s native Kintyre, where the painting is set.

William MacTaggart: The Preaching of Saint Columba.

Image credit: Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council.

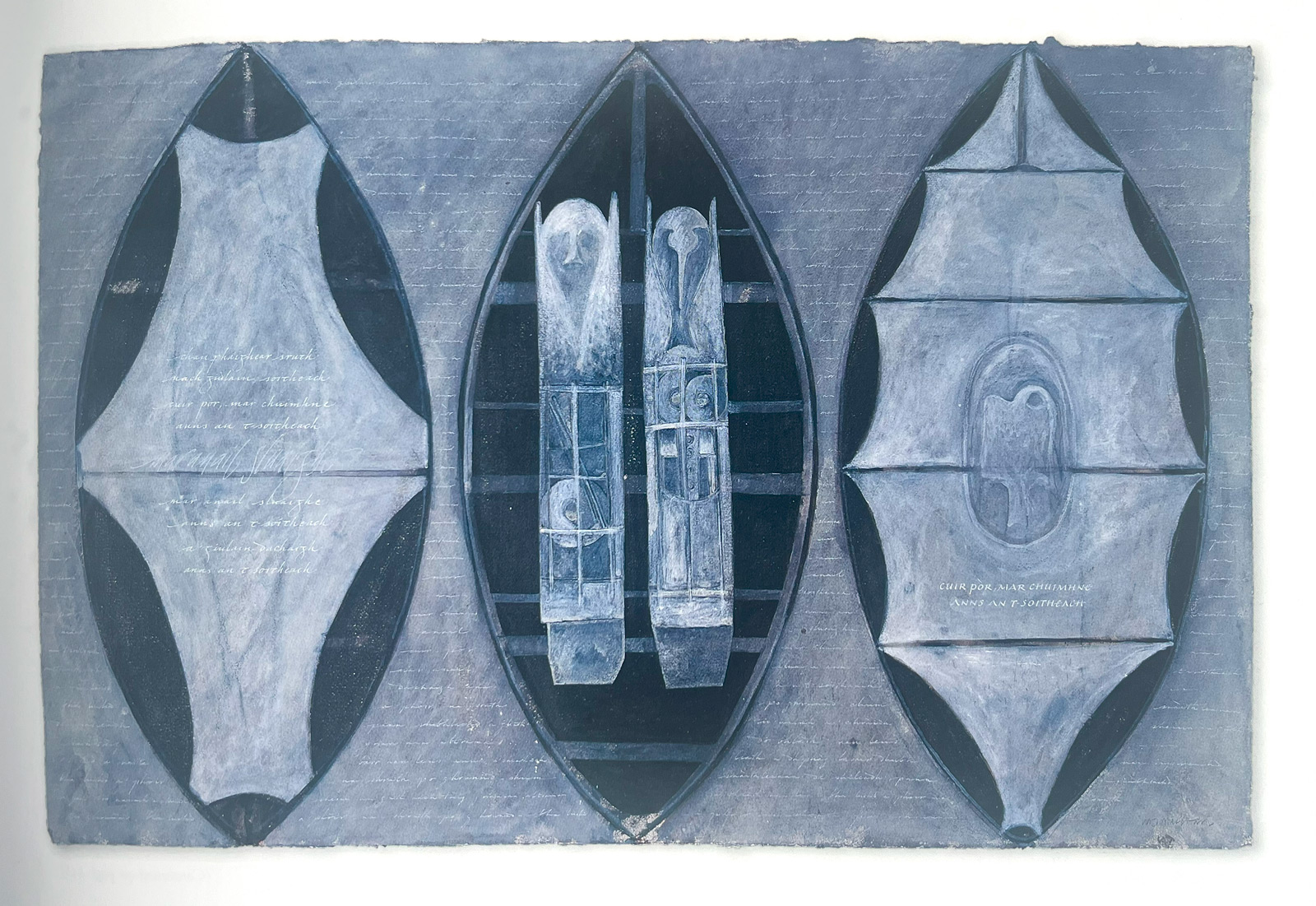

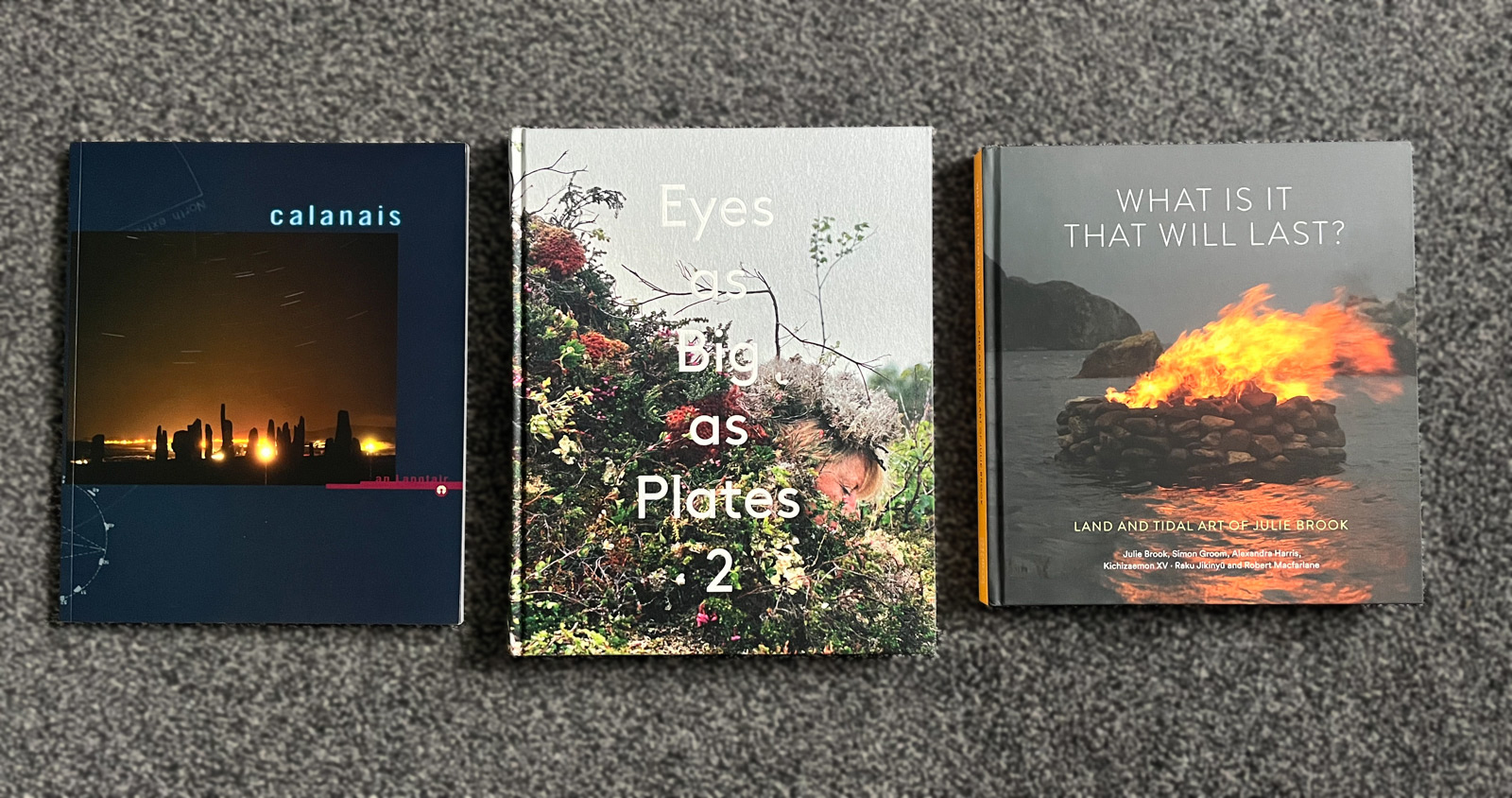

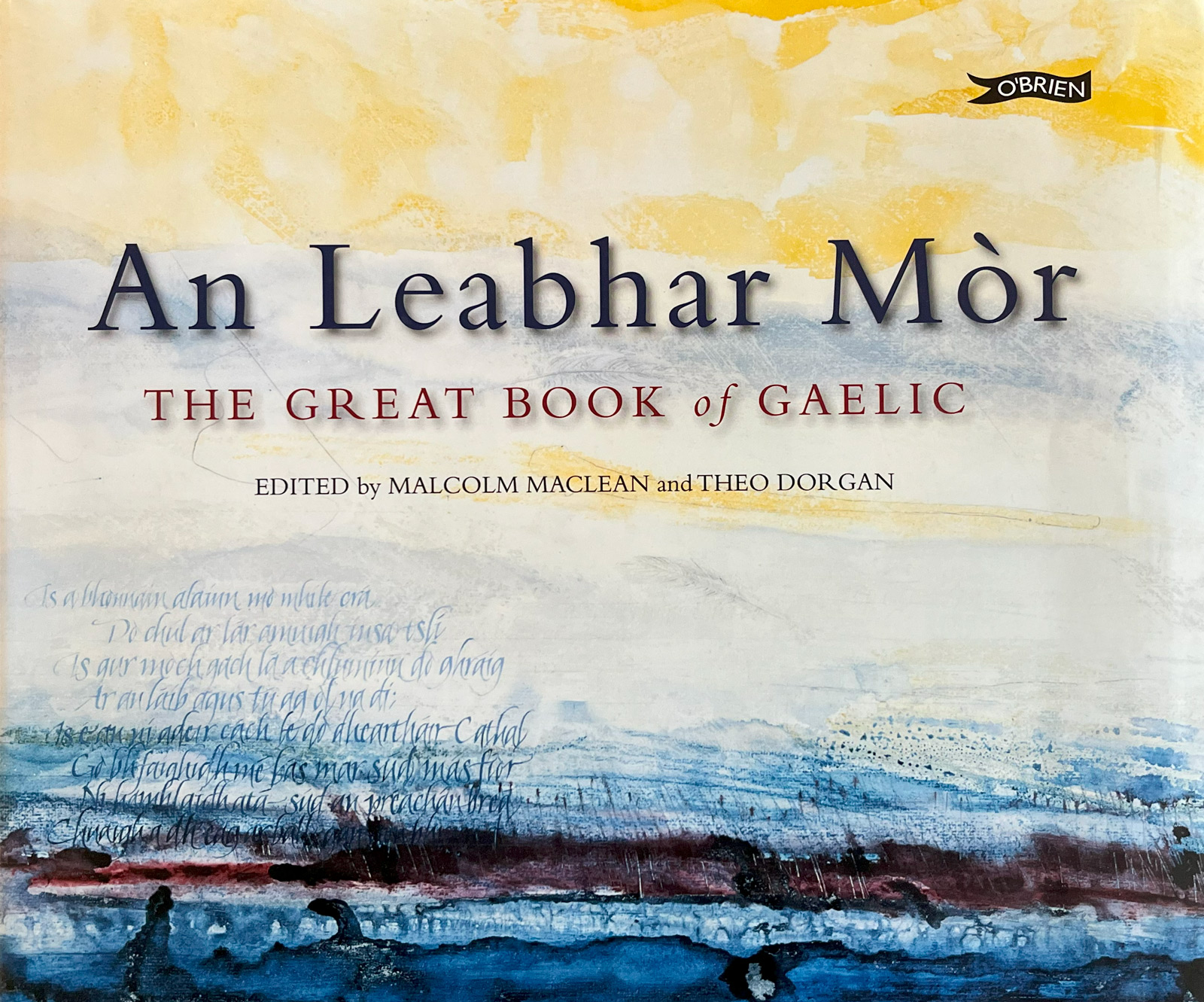

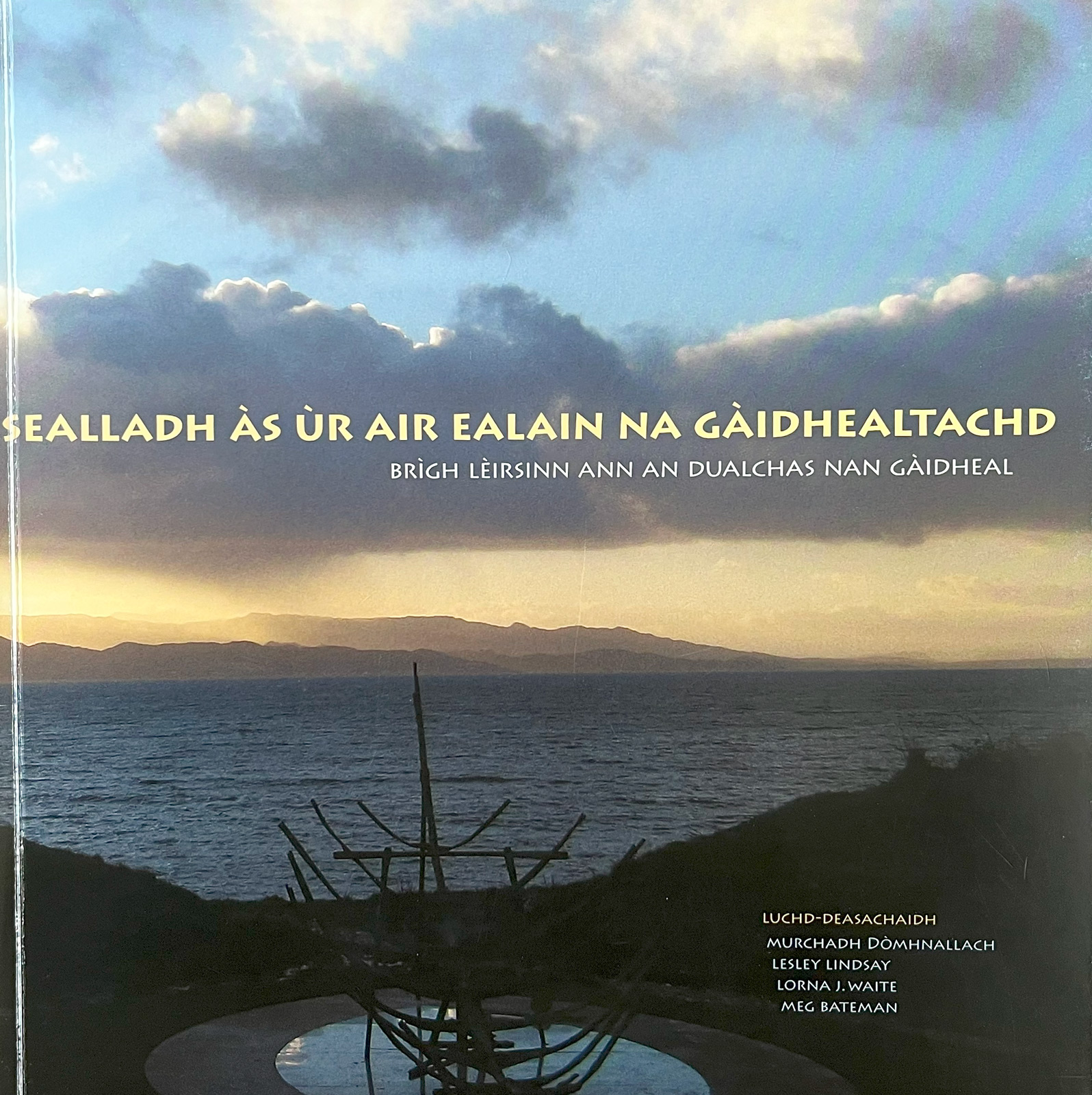

In 2010 the painting was featured in an exhibition in which Will Maclean was closely involved. That exhibition was Uinneag Dhan Àird an Iar: Ath-lorg Ealain na Gàidhealtachd / Window to the West: the Rediscovery of Highland Art, at the City Art Centre and it ran from November 2010 to March 2011[1]. I remember Will Maclean studying McTaggart’s representation of the boats that Columba would have sailed in. Like McTaggart, Will Maclean has explored the theme of the extended Scottish and Irish Gaidhealtachd in a number of his works. A crucial one that I want to consider here is an image made in collaboration with the poet Aonghas Macneacail, for the 2002 project An Leabhar Mor / The Great Book of Gaelic. [2] Both Maclean and Macneacail were advisors to that project which brought together artists, poets, calligraphers and typographers from Ireland and Scotland.

'Aonghas Dubh Macneacail' from The Great Book of Gaelic - Artist Will Maclean, Caliigrapher Frances Breen.

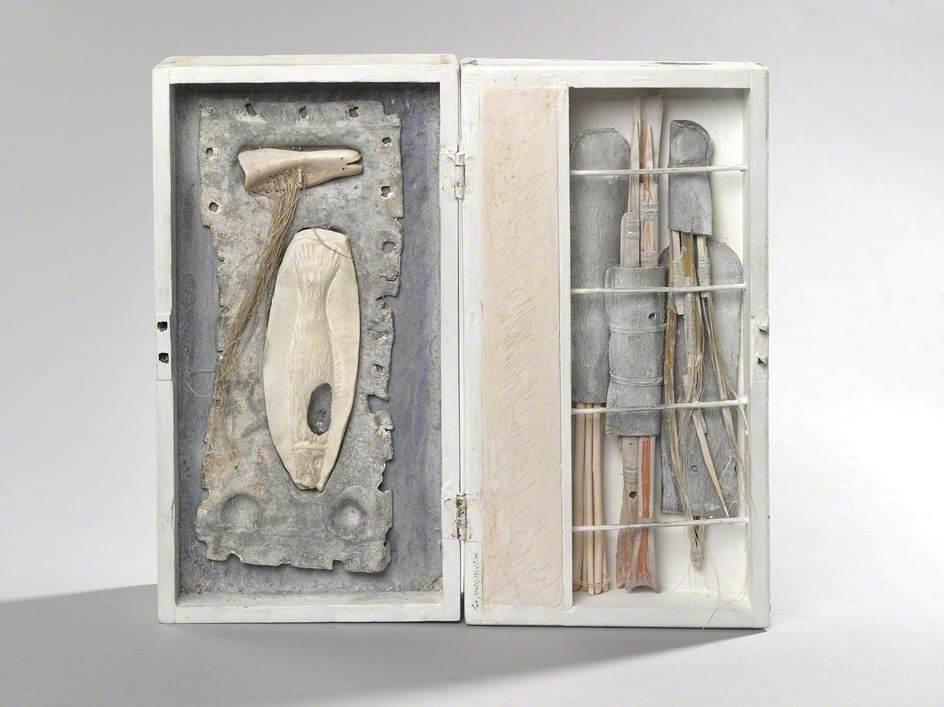

Maclean’s work takes as the basis of its form the idea of the leather skinned currach in which Saint Columba travelled to Scotland. The poem that Macneacail wrote is subtly integrated into the work as a whole by the calligrapher Frances Breen. It thus forms an integral part of the work, but the poem itself was inspired by an earlier assemblage by Will Maclean. That work was Voyage of the Anchorites dating from 1996. It referred to the early Christian figures travelling between Ireland and Scotland. Voyage of the Anchorites is now part of the collection of the Scottish Parliament, and there is a short but informative talk about it that you can find on youtube. There Will Maclean explains his references to every tool and magical folkloric object, all held within the form of a leather skinned Celtic boat. Knowledge is being transmitted not just through people, but through material culture.

Voyage of the Anchorites - Will Maclean, Image credit: Scottish Parliament Art Collection.

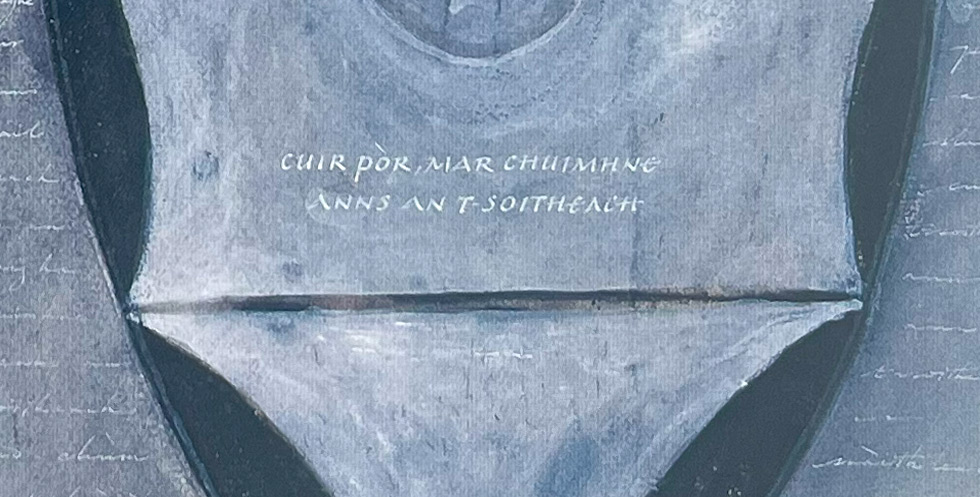

In the image for the Great Book of Gaelic one can see the absolute integration of word and image. Although completely of its own time, it is a psychological reflection of the integration of word and image one finds in early Celtic manuscripts. As I have noted a crucial third person involved in the work was the calligrapher Frances Breen.

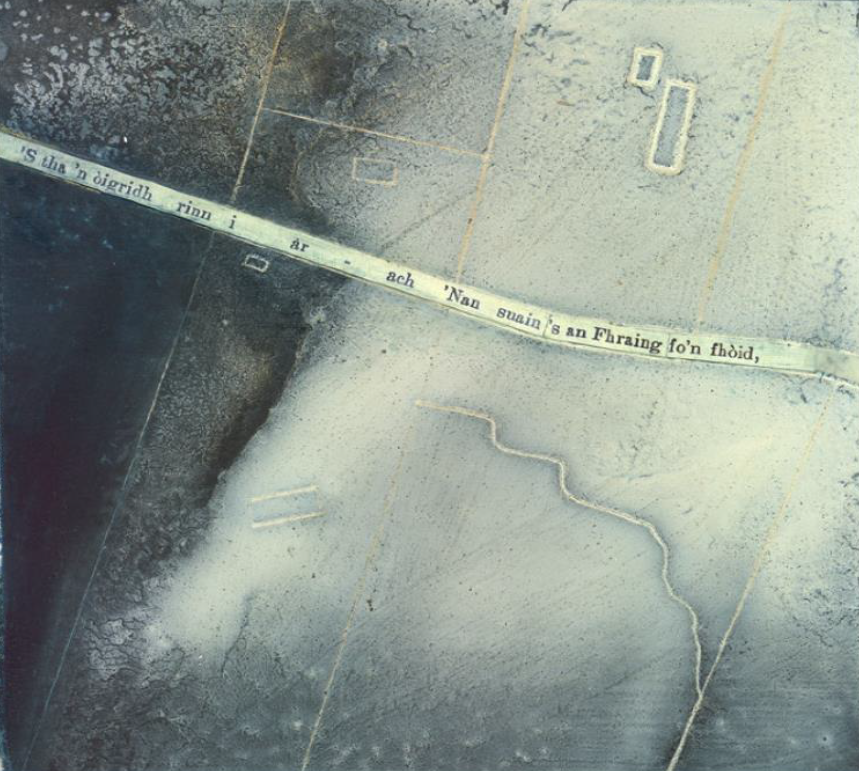

Detail of calligraphy by Frances Breen from the Great book of Gaelic.

This detail shows her lettering of a Gaelic phrase from Aonghas Macneacail’s poem which can be translated as:

put a seed, like memory,

into the vessel [3]

Such notions of seeding, of memory, and of culture are crucial to both the artist and poet. Will Maclean was born in 1941 and grew up in Inverness, where his father was Harbour Master. His father was a native Gaelic speaker from the crofting village of Polbain in Coigach, not far from Ullapool, and his father’s family was, through the 1940s and 50s entirely Gaelic speaking. Maclean feels his own loss of Gaelic as a child in Inverness, as a deeply personal loss. The Great Book of Gaelic was an effort to reverse such losses through art and poetry. It attracted considerable international interest, touring widely. I remember Aonghas Macneacail reading his poetry beside Will Maclean’s work at Cape Breton University in Canada, in 2009. The work hanging above that of Will Maclean was Frances Walker’s exploration of a poem by Iain Crichton Smith, a further indication of the strength of the Great Book project. I remember Aonghas Macneacail again, this time discussing Will Maclean’s image in detail at a symposium linked to the Cape Breton University exhibition. With me listening as Aonghas discussed the image was the originator of the Great Book project, Malcolm Maclean. Although not ignoring hope for the future in that transmission of knowledge of language and culture, there is also strong reference in Macneacail’s poetry to the post Culloden oppression of the Scottish Highlands.

Frances Walker’s exploration of a poem by Iain Crichton Smith, from the Great book of Gaelic.

He writes of that depeleted state of the Gaidhealtachd

this ruin remained, like a husk

awaiting its seed

He sums up that notion in another poem, ironically titled in its English translation ‘A Proper Schooling’. He writes: ‘when I was young / it wasn’t history but memory’, by which he is contrasting the so-called history taught in the schools he had to attend with the way his own history and language was not simply completely ignored but actively suppressed. Instead, it was the memories of members of his own community, which preserved that language and history. It is such actively maintained ignorance that both Aonghas Macneacail and Will Maclean stand against in their work. Both are well aware of the atrocities committed against Highland communities in the name of progress and improvement. Maclean’s great-great-grandfather was two years of age when the family were cleared from Coigach.

Crannghal, Will Maclean, Arthur Watson and Eden Jolly. Image credit: Sabhal Mòr Ostaig.

One finds Maclean taking exploration of Highland cultural heritage further in a bronze sculpture from 2006 made in collaboration with his colleague at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Arthur Watson. I refer to the Crannghal sculpture in Skye which echoes the form of his Great Book of Gaelic work. It was made for the new campus at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the Gaelic College of the University of the Highlands and Islands. Will Maclean was much more than a commissioned artist here for he has been a key advisor to the college over the years, not least with respect to establishing an artist in residence scheme. The word ‘crannghail’ is given a number of meanings in Dwelly’s dictionary, for example: wooden framework, wooden skeleton or substructure, latticework, rigging, etc. It was all those notions of construction that Will Maclean was engaging with, rather than any simple representation. The inclusion of castings of scattered tools on the granite base the sculpture makes a crucial point for the artists made the willow frame of it using only the tools that would have been available in the days of Saint Columba. It was cast in bronze by Eden Jolly at the Scottish Sculpture Workshop. Thus, the sculpture is not intended to be an evocation of the form of Saint Columba’s curragh, but rather, moving on from that notion of representation, an expression of what sort of sculpture you can make with traditional tools available in the sixth century, and a suitable supply of wood and twine. The finished bronze is thus a kind of recording of a performance of traditional methods. So, it is about traditional skills, but, by the same token, it is about potential loss or revival of traditional skills. As such it has profound resonance with the cultural purposes of the Gaelic college that commissioned it.

No less a figure than Albert Einstein identified a proper knowledge of tool use as fundamental to education. Einstein knew that such integration of hand and eye was fundamental to effective thinking, and so does Will Maclean [4]. Maclean and Watson went on to make a related piece at the Window to the West exhibition at the City Art Centre in Edinbhurgh in 2010. I remember seeing Will Maclean absolutely in his element creating that analogous but different structure from the same materials at the City Art Centre. So, tool use is fundamental to Maclean’s work. He trained as a painter in Aberdeen, but he found his feet as an artist when he began to make boxes and assemblages. A glance round Maclean’s studio makes that emphasis clear. His studio is a workshop full of tools. From an art historical perspective, he was inspired not least by the assemblages of the American artist Joseph Cornell, but at the same time his background was, like that of many so Highlanders, intensive contact with the tools needed on an everyday basis for crofting and fishing. It was in Polbain that Will Maclean learned the disciplines and rituals of small boat fishing for food, peat cutting, and croft work that is reflected in so much of his work.

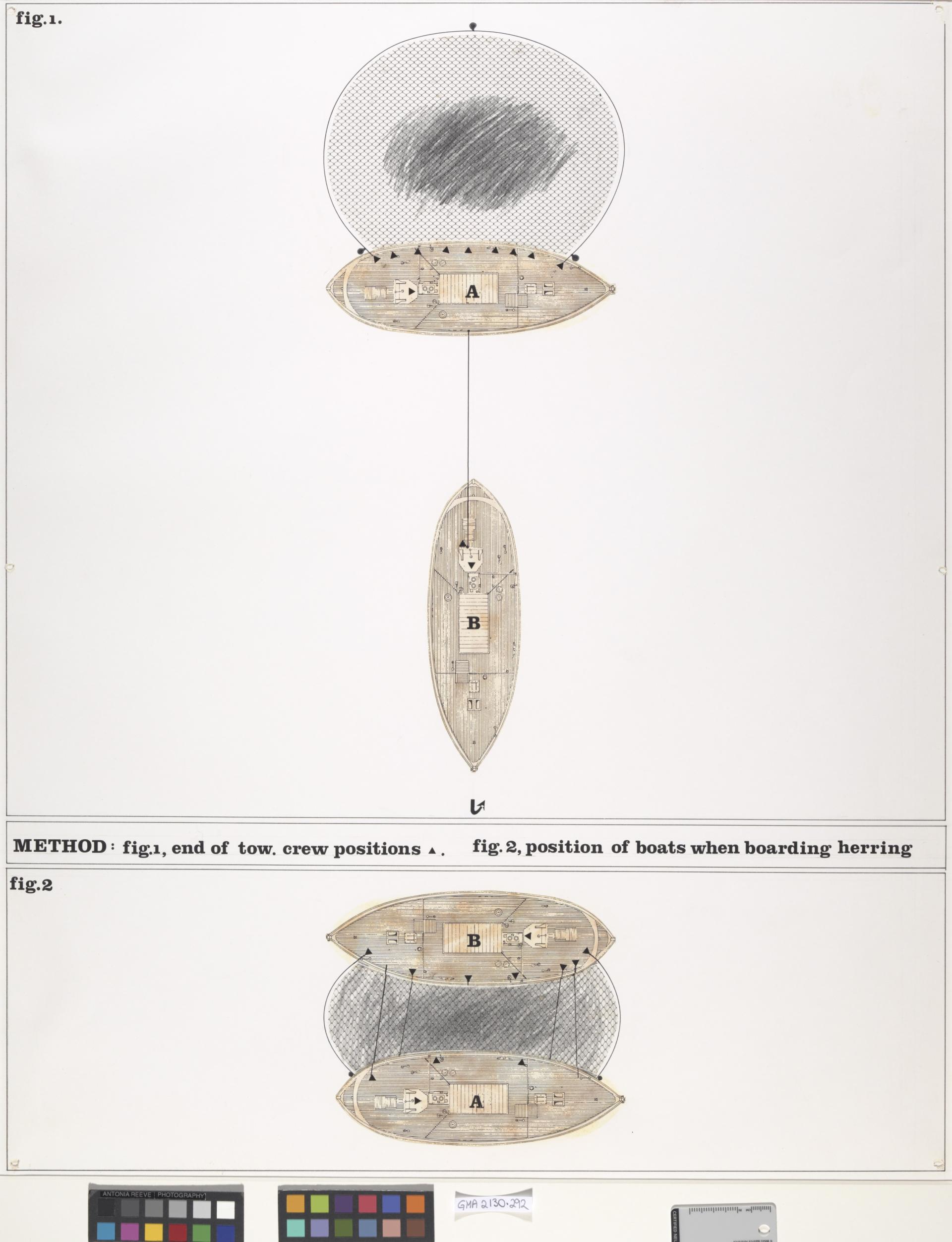

Toolbox Fisher Shaman, Will Maclean. Image credit: The Fleming Collection

Thus, Will Maclean brings that experience of tool use into his art, reflecting deeply on it, often from a cross cultural perspective, but all given depth of understanding by his immediate knowledge of Highland fishing practices in particular. That is where his pioneering Ring Net Project from the 1970s comes in for it documents and responds to a type of fishing that Maclean had himself been part of. His uncle in Kyleakin in Skye would take him out on his fishing boat, sometimes for days at a time, and when Maclean left art school he worked as a ring net fisherman for several months. The point here is that he didn’t plunge into the Ring Net project as an outsider, he knew the structure of that type of fishing. He remembers that ring netting at that time was absolutely integral to the community of Kyleakin, but also right up and down the coast, and he remembers that so many of these West coast communities had ring net boats, which provided significant support for those communities. At the suggestion of Richard Demarco he applied to the educational trust set up by Sean Connery, for funding to make a visual record of ring net herring fishing. So Maclean spent 1972 on and off the boats drawing and photographing, compiling a mass of information and teaming up with the Campbeltown poet Angus Martin, who was collecting material from the Campbeltown area, which was where ring netting began. The Third Eye Centre in Glasgow put on Maclean’s exhibition in 1978, and it toured, not least to the Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh. It is now in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland.

The Ring-Net (Ring-net Herring Fishing on the West Coast of Scotland), Will Maclean.

Image Credit: National Galleries of Scotland.

During that period Maclean was also part of Richard Demarco’s Edinburgh Arts journeys, and one of the destinations for those journeys was the studio of the American painter Jon Schueler, who had spent time on the West Coast since the 1950s, and in due course bought a house close to Mallaig. He painted there fulltime from 1970 to 1975, and thereafter visited every year. Schueler is an extremely interesting figure in terms of Highland art. He is usually described as a second-generation Abstract Impressionist, a bit younger than his American contemporaries Clifford Still, Jackson Pollock and Marc Rothko, but very much part of the same milieu in California and New York. But his significance in terms of the Highlands is as the artist, from the 1950s onwards, who most clearly adapted abstract paint fields to landscape and seascape, recognising the very close relationship between what we call representation and what we call abstraction. This is particularly true of his work responding to the light, colour and weather of the Sound of Sleat between Mallaig and Skye.

Storm at Sea Remembered, Romasaig. Jon Schueler (1916–1992)

Image Credit: Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

In one work I show here, Storm at Sea Remembered, Romasaig, dating from 1974 and in the collection of Dundee Museums, Schueler is inspired by the weather of the Sound of Sleat during the exact period Will Maclean was involved in the Ring Net project. Maclean has fond memories of visiting Schueler during the 1970s when he was ring net fishing, and the boat was moored in Mallaig. In a drawing by Maclean’s from that period, he shows something he would have been very familiar with, the difficulty of landing a catch in bad weather. The image is made all the more acute because it is the drawing of an artist who is also a fisherman. There is a profound resonance here not just between Maclean and Jon Schueler in the 1970s, but, going back to the 1890s, between Maclean and William McTaggart. I refer in particular to William McTaggart’s painting from 1890, The Storm. Like Maclean’s work it shows the everyday danger the weather presents to the activity of fishing, as a rescue boat is launched to aid a fishing boat trying to return home to Carradale in Kintyre during a storm. The concern for community is identical to that of Maclean, and also, like Maclean, McTaggart is at the forefront of the art of his time, indeed his technique seems to look forward to John Schueler.

The Storm: William McTaggart.

Image Credit: National Galleries of Scotland.

So far I have indicated analogies between Maclean’s work and that of McTaggart, and pointed out that those analogies are driven by their shared knowledge of Highland community. But there is one work by McTaggart that is more than analogous with Maclean’s work, for Will Maclean makes explicit reference to it. That is McTaggart’s The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship, painted in 1895.

McTaggart’s The Sailing of the Emigrant Ship.

Image Credit: National Galleries of Scotland.

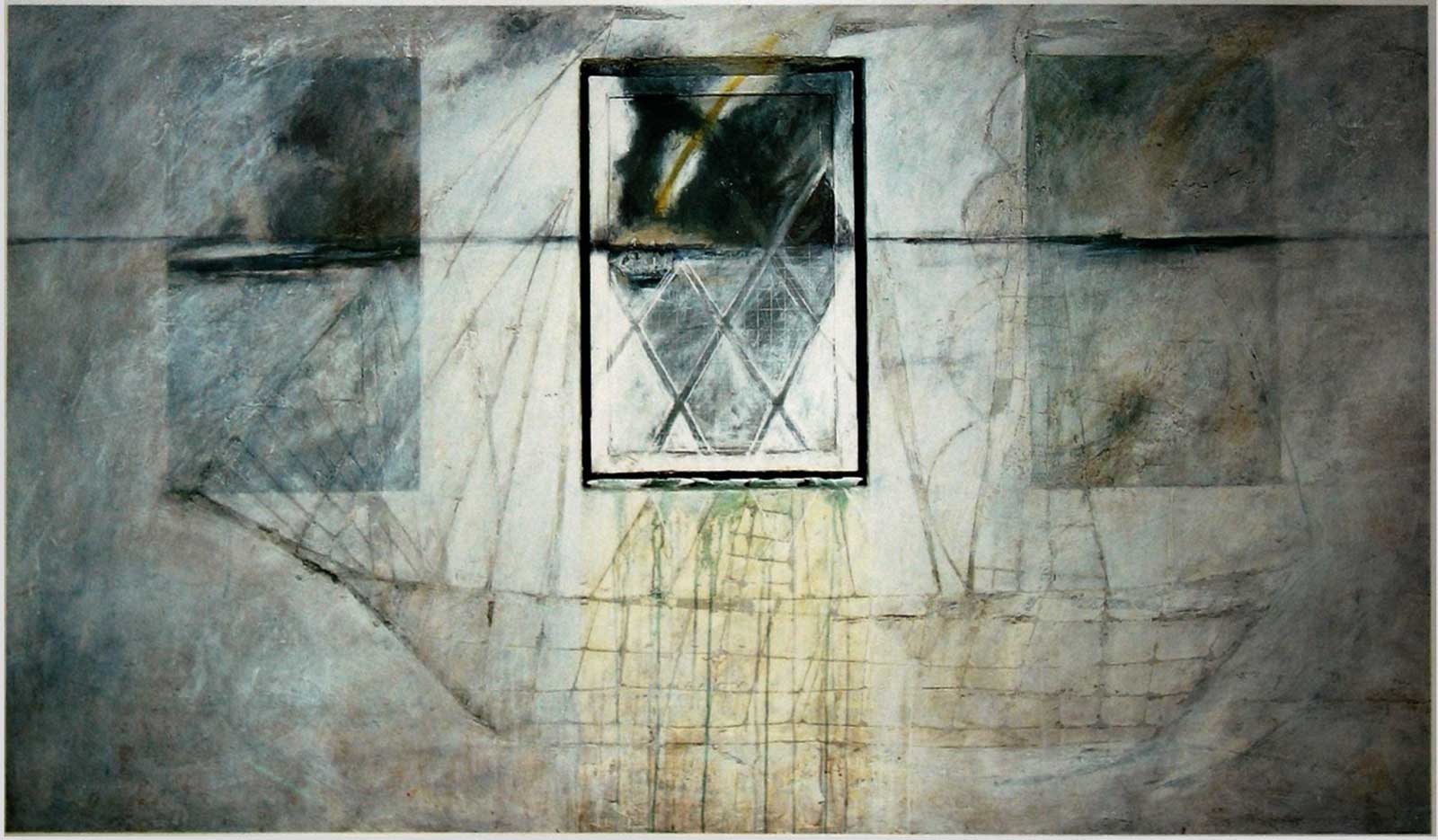

The painting shows an emigrant ship leaving Kintyre during the time of McTaggart’s childhood in the 1830s. It is thus a memory of Highland clearance, not just of emigration. In his own work, entitled simply Emigrant Ship, Maclean picks up on both McTaggart’s title and his image. Maclean’s Emigrant Ship has many layers of meaning, and if you look carefully within the central window, on the left had side there is a small image of a ship, which in its relation to the whole is immediately reminiscent of McTaggart’s painting. At the same time Maclean makes that ship image a reference not only to McTaggart, but to the whaler’s art of scrimshaw that is to say an image engraved on whalebone or walrus ivory, a traditional seafarer’s art form. That double reference, to a great pioneer of modern art in Scotland, and to a traditional sailor’s art form, is a deepening of allusion typical of Maclean. But there is much more here, for not only the ship image, but the window itself is a reference to Highland clearance, the forced removal of Highlanders from their homes. The window reimagines one of the most evocative images of clearance, namely the east window of Croick Church in Sutherland. On that window the evicted tenants of Glencalvie, taking refuge in the churchyard in May 1845, scratched messages of despair. But in his Emigrant Ship Maclean goes even further for he brings the Croick window image together with a graffiti image, used as a background, perhaps itself of an emigrant ship. That image was scratched on the wall of a deserted schoolhouse in a cleared settlement in northern Mull. A poignant image in itself and the more so when united with those other references to Highland clearance. And as we have seen, reflected in the window is that other emigrant ship, firmly embedded not only in Highland history but in the history of Scottish art. Thus, via McTaggart, Maclean makes clear the significance of visual art to the exploration of historical and contemporary issues.

The Emigrant Ship, 1992, mixed media on board with slate and wood, private collection

Some years earlier Maclean had made a related work focused on a window entitled Inner Sound. It dates from 1984, and it is a construction measuring about 18 inches across. It shows the boarded-up window of a deserted house. Looking out through this window we see the conning tower of a submarine. In that work Maclean draws together two essential and interconnected elements of Highland history: clearance and militarism. The title of this piece is Inner Sound, and this gives us a specific geographical location for the work. The ‘Inner Sound’ in question is the stretch of water between Raasay and Applecross, with which in his days as a fisherman Maclean was very familiar. But there is a hint also of a psychological inner sound that we should be listening for. That sound is the sound of the Gaelic language.

Inner Sound, painted wood, 1984, private collection.

One of Maclean’s most direct responses to Gaelic is his major etching series from 1991, A Night of Islands, which was given an entire wall of the City Art Centre in the Window to the West exhibition in 2010. Maclean makes a very fine response to a poem by Meg Bateman, Loss of Gaelic. In her poem Meg Bateman, in her own English translation, writes of ‘a despoiling of humanity / for which there can be no reparation’, a comment which sums up the ethos of so much of Maclean’s work. I remember seeing Meg Bateman with her own work and Maclean’s response to it. Above it was positioned a work by another renowned Gaelic poet, Derick Thomson. That poem is Strathnaver, and in it, Thomson reflects with brutal irony on the destruction of people’s homes and livelihoods during the clearances in Strathnaver in the mid nineteenth century.

A Night of Islands, Will Maclean. Image Credit: The Paragon Press.

The locating in Raasay of the window shown in Maclean’s Inner Sound gives us another clue as to how we should read it, for this boarded window is a specific link to two poems by Will Maclean’s relative, the poet Sorley MacLean. The first of those poems is Hallaig, first published in 1954. There we read, in the poet’s own translation from the Gaelic: ‘The window is nailed and boarded / through which I saw the West’. So, obviously enough, this is no tourist view, this is a view mediated by destruction of community. I have already referred several times to the Window to the West project and the exhibition at the City Art Centre in 2010. It is from Sorley Maclean’s poem that the title for that project came, at Will Maclean’s suggestion. For Will Maclean, part of that process of repairing Sorley MacLean’s nailed and boarded windows must involve understanding visualisations and revisualisations of the Highlands, and Will Maclean’s art remains at the heart of that process. The other Sorley Maclean poem to which Inner Sound refers is Screapadal, a passage of which, in Sorley’s own translation, reads:

‘A seal would lift its head / and a basking shark its sail, / but today in the sea-sound / a submarine lifts its turret / and its black sleek back / threatening the thing that would make / dross of wood, of meadows and of rocks / that would leave Screapadal without beauty / just as it was left without people.’

And while that whole passage is an appeal against militarism that final line is crucial ‘just as it was left without people’ for this again is a reference to the clearance of communities from the Highlands.

Maclean’s image helps us to understand the parameters of stereotypical images of the Highlands such as Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen. Where Landseer’s deer (and the estate surrounding it) existed to serve the pleasure in hunting of people who did not need to eat its meat, Maclean’s window is symbolic of all those windows which once sheltered people who needed to hunt deer for food but could not do so because of inequitable land ownership.

Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen.

Image Credit: National Galleries of Scotland.

In 1887, three decades after Landseer painted the Monarch of the Glen, this tension was sharply expressed in the Isle of Lewis, when the men of Pairc put their own human rights before the legal rights of the estate owners and hunted the deer. It is that deer raid of November 1887 which is commemorated by Will Maclean’s memorial cairn built in 1994 at Balallan in Lewis. That was the first of a remarkable series of land struggle memorials. I spend the final part of my talk considering their significance.

Memorial to the Pairc Deer Raiders: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

James Crawford and John Norgrove and Will Maclean.

A859, Baile Ailein, Lewis, Western Isles. Image credit: Carsten Flieger / Art UK.

One finds a resonance in the structure of Maclean’s Ballallan work with the great iron age brochs such as one finds at Carloway in Lewis. So there is a deep historical and indeed prehistorical embedding in Maclean’s thinking. A key point is that these memorial cairns, although of course they memorialise events of historical land struggle, are much more than this, for they link strongly not only to the roots of community in prehistory, but to the present, in the context of the inequitable distribution of land in the Highlands, which is very slowly changing as more community buy-outs are made. The Balallan cairn was completed in 1994. That is just one year after the Assynt crofters trust had successfully bought out the estate they lived on in Wester Ross. So, that cairn, with its specific recording of actual struggle is not a nostalgic memorial but is absolutely to the point with respect to current land use issues in the Highlands. Two more cairns, marking other aspects of the Lewis land struggle, followed at Aignis and Gress, both completed in 1995. Those were completed two years before the Isle of Eigg Trust successfully saved that island for its inhabitants in 1997. Maclean explains how he went back to the genesis of what happened in the land struggle at the places he was working in, what the particular struggle was about, ang the particular circumstances of the people at the time.

Aiginis Farm Raiders Monument: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

Will Maclean and John Norgrove and James Crawford. Image credit: Carsten Flieger / Art UK.

Memorial Cairn to the Gress and Coll Raiders: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

Will Maclean, John Norgrove and James Crawford. Image credit: Carsten Flieger / Art UK.

As will already by obvious, for all that Maclean often makes personal and very individual works, he is also one of the great artist-collaborators. For example, these cairn projects drew on the engineering skill of John Norgrove, and of particular importance to the final impact of each cairn was the stone masonry of James Crawford. Maclean speaks with warmth about being brought into community working groups in which he became simply ‘the artist’. For the first time ever, he says, he had a place in a group of people as a functioning artist. Maclean talks of ‘each community had its own identity and its own committee and its own ideas’. The community success of the cairn at Aignis is evident in the fact that the Point and Sandwick Trust has adopted it as a very effective logo. [the motto is coimearsnachdan comhla: community together].

Maclean’s description of the memorials as ‘cairns’ is also significant. It picks up on the ancient practice of marking places and events and memories with carefully constructed piles of stones. There are many such cairns in the Highlands. Some are from the prehistoric period, for example one prominent on the skyline overlooking Strathearn in Perthshire. It links up to standing stones miles away. The point is not to suggest that this or that cairn was a direct influence on Maclean, but simply to note that in his land struggle cairns he adopts a very traditional way of doing things which he transforms through his insight as an artist. The memorial at Culloden is another such Highland cairn. Made in 1881, it could be considered part of the romanticisation of the Highlands, but it is more appropriately considered as a reminder of the cultural trashing of the Highlands which followed the battle of Culloden in 1746, the cultural dynamic that leads to so much of Will Maclean’s work. The date of construction, 1881, is a significant one for it is during the period of an attempt to restore some equity to Highland land use, namely the Napier Commission into crofting, which reported just three years later.

The memorial at Culloden. Image Credit: C. E. Morton.

Finished drawings exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy, 2007.

So, Will Maclean’s cairns give a starting point for a wider interrogation of Highland history and indeed prehistory. These drawings of the first three were at the heart of the Royal Scottish Academy annual exhibition of 2007. Since then a fourth cairn has been built in Lewis. That most recent land struggle memorial, An Suileachan, was completed at Reef in Valtos in 2013, reflecting the successful community buyout of the Valtos peninsula in 1999 and marking the centenary of the 1913 attempt by men from Reef to re-establish crofting, after the community had been cleared to make way for sheep in the mid-nineteenth century. The men were arrested but eventually successful in their aims in 1921. On the one hand the structure can be seen as celebratory rather than defensive, a place that not only memorialises struggle for land, but a place where the community of today can meet. But at the same time, it a construction reflecting not only tough political struggle, but the tough landscape of peat and rock within which those struggles took place. In conversation Maclean quotes a line from Hugh MacDiarmid, ‘all is lithogenesis’, drawing attention to a timeline for the monument which is geological as well as human. The name An Suileachan, gives further pause for thought for it means: the warning, the lesson, the eye-opener. So, what might be that warning, that lesson, that eye-opener, to which the monument refers? It is straightforward. Local people should own the land, and the warning is drawn from the experience of the people of the Valtos peninsula. Another ‘warning’ from An Sùileachan, is the one that has been running through this talk, namely that loss of people is loss of knowledge. Such knowledge is clear in every carefully laid stone of the monument’s walls, and the smithing of the fire basket within those walls that acts as both a hearth and a beacon.

An Sùileachan, Will Maclean and Marian Leven. Image credit: Carsten Flieger / Art UK.

An Sùileachan was designed by Maclean in collaboration with his wife Marian Leven, who is, like him, a distinguished member of the Royal Scottish Academy. Like so many of Maclean’s works An Suileachan takes collaboration for granted, and many others made significant contributions to the work, whether in the dry-stone construction by Iain Smith or the ironwork of the fire basket by Calum ‘Steallag’ Macleod. The monument has a remarkable central stone doorframe or gateway, a symbol in stone made by Jim Crawford, in the form of three monoliths which owe much to the prehistory of the area. Maclean reflects that ‘the main thing that holds the piece together is down to Jim Crawford, its builder, who discovered – when he was up and down in his boat – amazing stones that were lying under the water’. At low tide, Crawford discovered that these stones had been obviously chipped out and chopped up at some earlier time and then abandoned. The finding of those stones was crucial to the way the central arch of the monument was put together. But Maclean also notes that the jointing reflects an Inuit technique, and that is again a reminder of how important the insights of other cultures have been to Maclean. Taking the four cairns together you can see what an impressive series it is. The title of the final cairn, An Suileachan: the warning, the lesson, the eye-opener, seems to refer to them all, and perhaps we can take it as a motto for Maclean’s work as a whole, for so much of his work is an eye-opener about Highland history and culture. It is worth remembering that Maclean is a teacher as well as an artist. For so many students his teaching was literally an eye opener [5]. I remember him lecturing at the National Gallery of Scotland at a conference run by the Window to the West project as a precursor to the exhibition at the City Art Centre later that year [6]. He said of the Window to the West project that ‘it established a given that there is a visual thing as well as the oral one in the Highlands’. That is a reminder that it is standard practice in the oppression of any culture to deny the value not just of the language, but also of visual traditions, so restoring a proper visual appreciation of the Gàidhealtachd has been essential.

Will Maclean and Voyage of the Anchorites. Image credit: Scottish Parliament Art Collection.

And that is what Maclean has done with his art. He has played a key role,

absolutely at the heart of the re-energising of Highland art, from the 1970s to the present.

[1] Uinneag Dhan Àird an Iar: Ath-lorg Ealain na Gàidhealtachd / Window to the West: the Rediscovery of Highland Art, at the City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 20 Nov 2010 – 6 March 2011. It was curated by myself and Arthur Watson.

[2] An Leabhar Mòr / The Great Book of Gaelic, edited by Malcolm Maclean and Theo Dorgan, Edinburgh: Canongate, 2002..

[3] cuir pòr, mar chuimhne, anns an t-soitheach

[4] ‘I should demand the introduction of compulsory practical work. Every pupil should learn some handicraft. He should be able to choose for himself which it is to be, but I should allow no one to grow up without having gained some technique, either as a joiner, bookbinder, locksmith, or member of any other trade, and without having delivered some useful product of his trade.’Albert Einstein, quote to be found in margin of page 201 of French, A.P., ed., (1979) Einstein: A Centenary Volume, London: Heinemann.

[5] Edward Dwelly, The Illustrated Gaelic-English Dictionary, Glasgow: Maclaren, 1949, p. 194. [First published in 1911].

[6] State of the Art: Visual Tradition and Innovation and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland Thursday 24th to Saturday 26th June, 2010, Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, National Gallery of Scotland, The Mound, Edinburgh

Will Maclean and Voyage of the Anchorites. Image credit: Scottish Parliament Art Collection.

Will Maclean's importance in the development of Highland (and Island) visual art cannot be overlooked. An artist whose work is a must for the Hulabhaig collection (eventually), but for now, I'm delighted to be able to share this essay by Murdo Macdonald, Honorary Member of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture. Honorary Fellow of the Association of Scottish Literary Studies. Professor of History of Scottish Art, University of Dundee (Emeritus).

From a talk first given online by Murdo Macdonald to the City Art Centre, Edinburgh, in July 2022.

Essay by Murdo Macdonald : 29/Aug/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

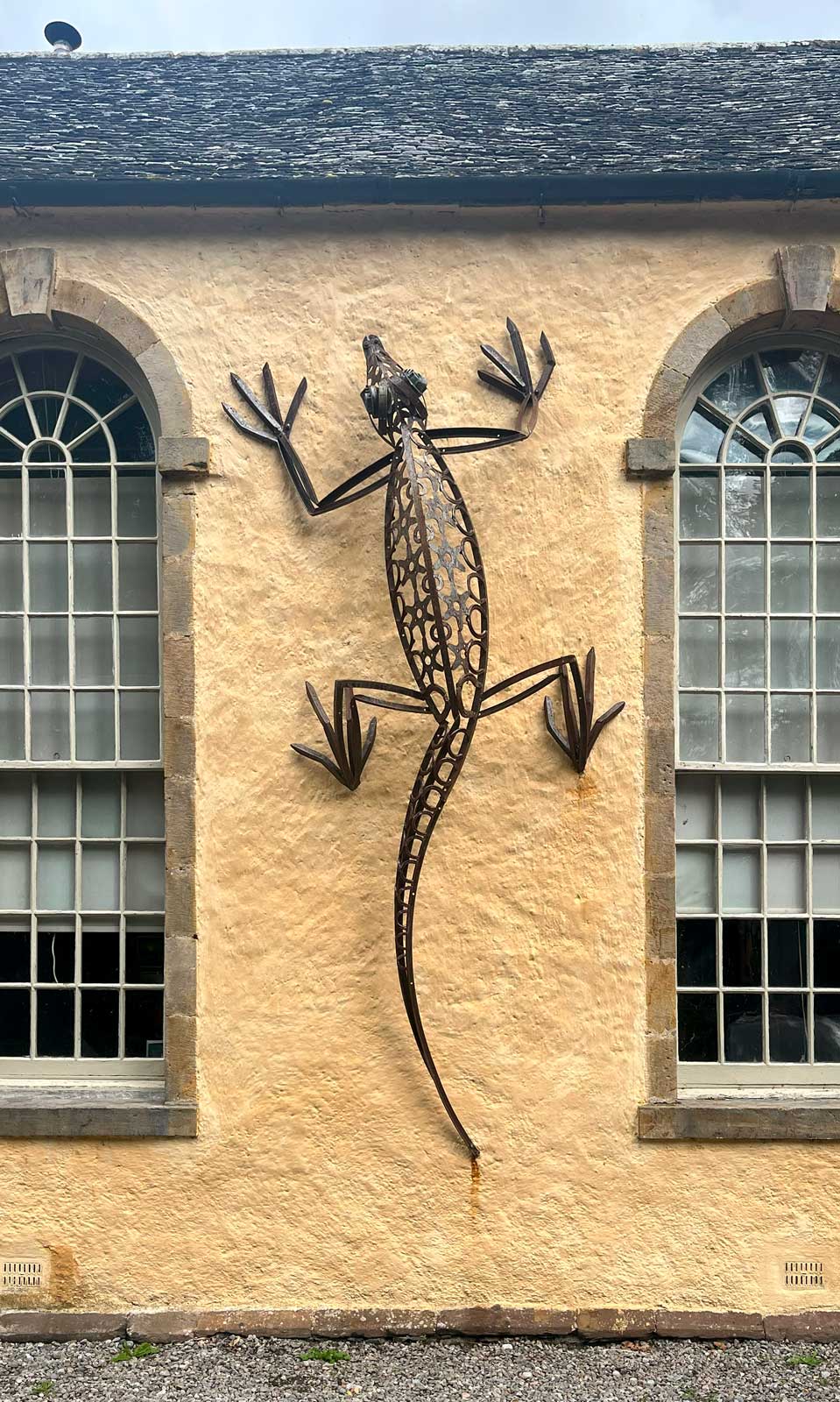

Johnathan Bell: Interconnected

The second exhibition by Isle of Lewis sculptor by Johnathan Bell at Baile na Cille Church.

Article by Andy Laffan : 25/Aug/2025

View Article

The Circle

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

Johnathan Bell: Interconnected

Interconnected: Johnathan Bell Sculptures.

16th August to 13th September 2025.

Baile na Cille, Uig, Isle of Lewis. @dusgadh_bailenacille

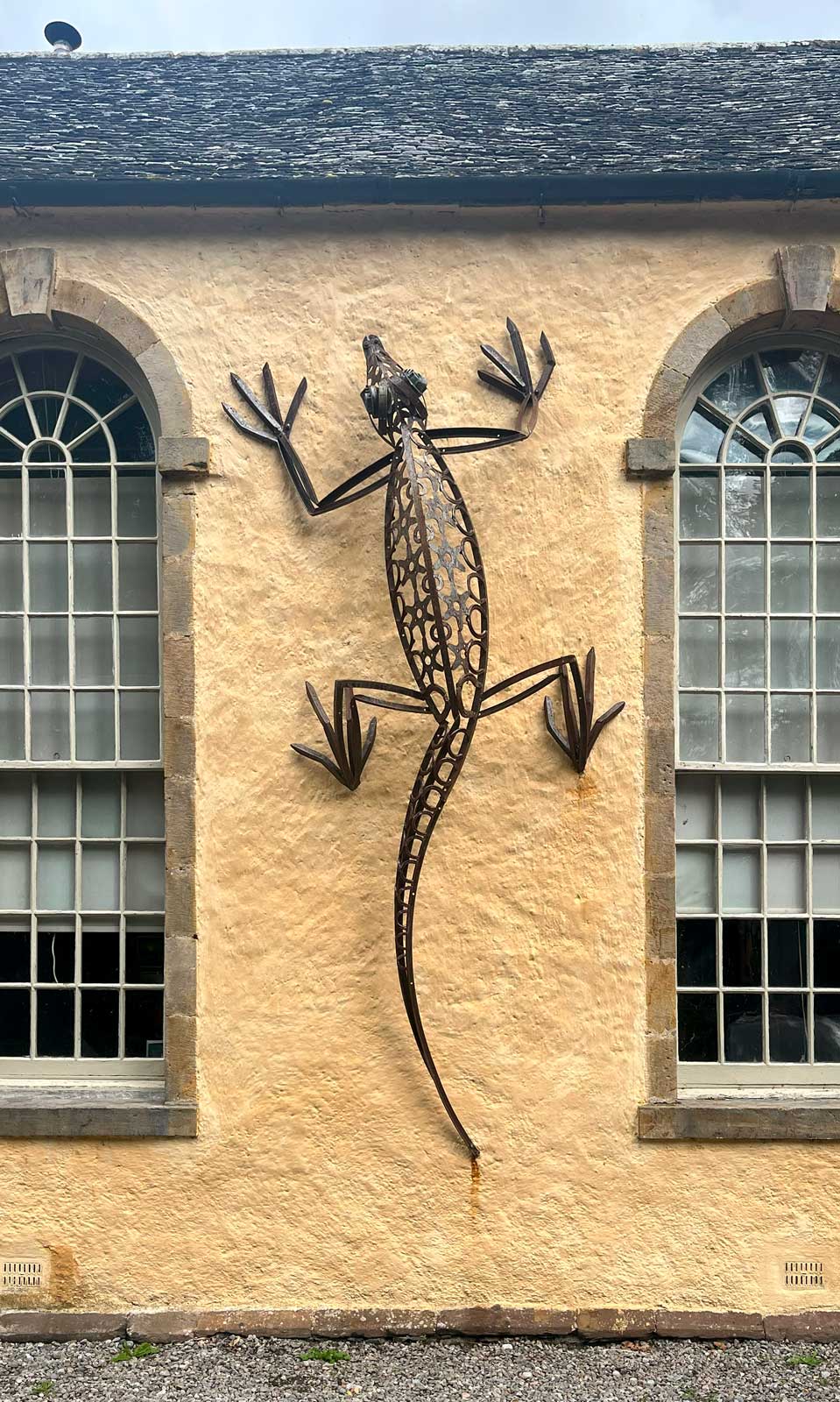

An eagerly awaited second exhibition for Isle of Lewis based sculptor Jonathan Bell.

Ever since I first saw hints of Johnathan’s work back in 2022 at his studio in Aird Uig I have been a fan. Back then he was preparing for his first show at Baile na Cille and at that time I was to curate the show. Sadly I had to pull out, but Johnathan continued with his work and produced an excellent inaugural show.

Cyclical Storm

This second show continues his investigations into the found detritus which washes up on our island shores on a daily basis.

The Circle

Turning rubbish into art is not a new idea but Johnathan’s delicate sculptures have a profound sensitivity unique in his work. Each found item, no matter how small, is meticulously cleaned, studied and carefully placed on a shelf in his studio, ready and waiting to be manipulated, paired or grouped eventually finding its own new final place.

Barrow Down

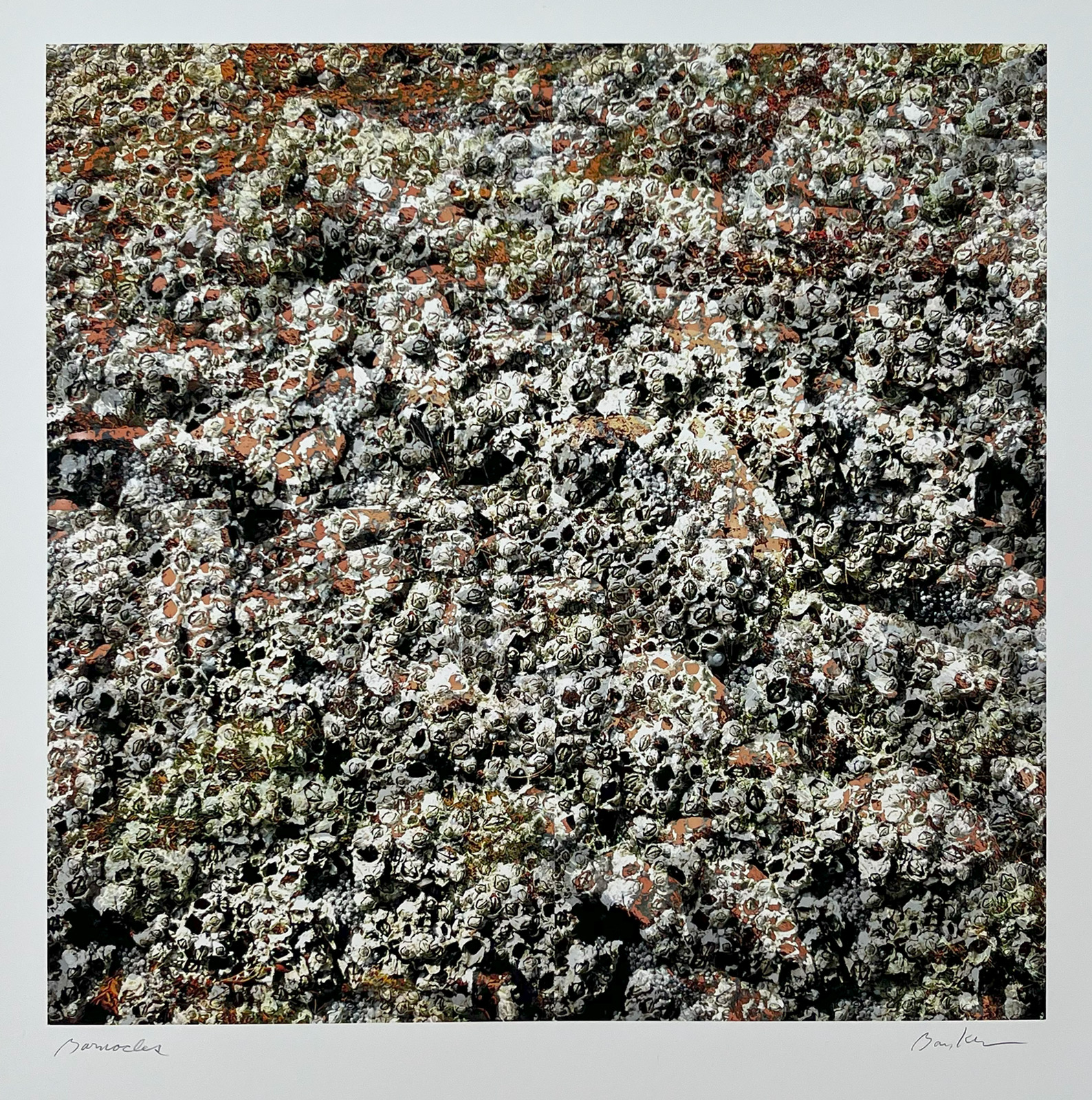

Pebbles, rope, bone fragments, sea weathered plastics, ground up rubber types, driftwood, sea glass, corroded metallic items and electrical components, once integral parts of our busy technological world, now part of the waste cycle slowly degrading into a world of micro plastics in a sea of industrial chemicals, polluting our oceans, killing wildlife, finding it’s way into our own food chain and even seeping into our own body cells and perhaps DNA.

Compass 2

Johnathan’s work interrupts the cycle, each item collected finding its new place, carefully aligning, connecting and merging with others, all coming together as one, one artwork, to be admired, owned, revered, reinterpreted and even valued once again.

Piercer

Each item then becomes a part, like an ecosystem creating an environment, full of life and hope, his sculptures are blank statements ready for interpretation, reluctantly titled to provide hints, but it’s the effect they have on the viewer which excites both Johnathan and myself the most. Visitors including tourists, locals, artists and even ministers all eager to see their own visions in the final forms. Each taking away their own thoughts, considerations and experience as memories of this unique encounter with Island Contemporary Art at its finest.

Temple

Delighted to now include this sculpture in the Hulabhaig Collection of Island Contemporary Art.

The Sum of Our Parts (Detail)

The Sum of Our Parts

Installation at Baile na Cille

Interconnected: Johnathan Bell Sculptures, continues to 13th September 2025.

Baile na Cille, Uig, Isle of Lewis.

All enquirues to Dusgadh:

fiona.simes.art@gmail.com

@dusgadh_bailenacille

The Circle

The second exhibition by Isle of Lewis sculptor by Johnathan Bell at Baile na Cille Church.

Article by Andy Laffan : 25/Aug/2025

Comments:

We would love to hear from you if you have enjoyed this article. Please add your email address and we will let you know when we post new articles.

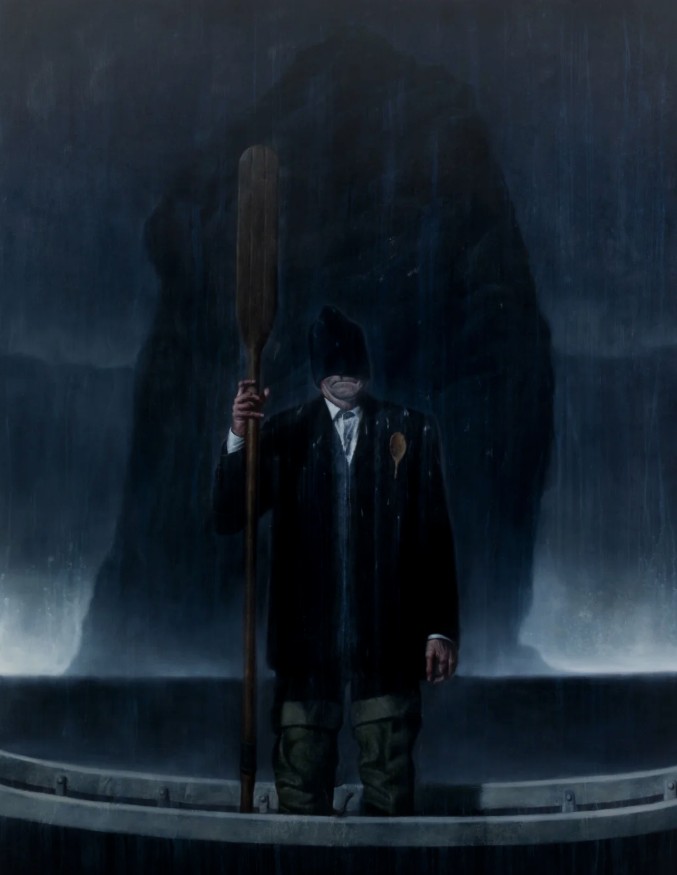

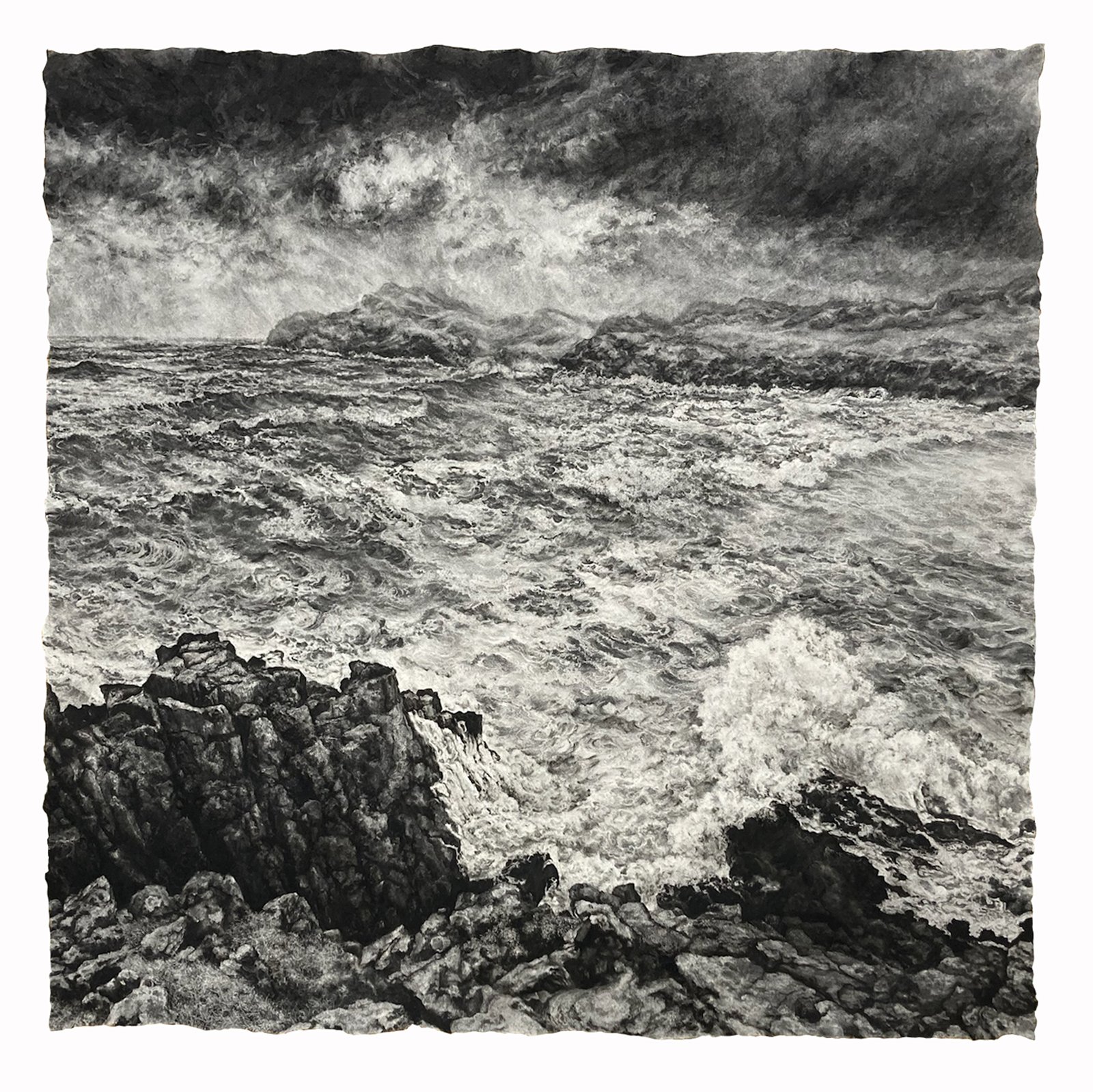

Ken Currie – An Turas: The Crossing

Guest writer Mike Donald reviews An Lanntair's latest exhibition.

Article by Mike Donald : 30/Jul/2025

View Article

Image credit, Flowers Gallery, London.

Hulabhaig Article: Island Contemporary Art

Ken Currie – An Turas: The Crossing

Colony (Dyptich), 2024